Revisiting ‘The Miraculous Adventures of Edward Tulane’

A children’s tale about a selfish rabbit doll who learns to love teaches us invaluable lessons.

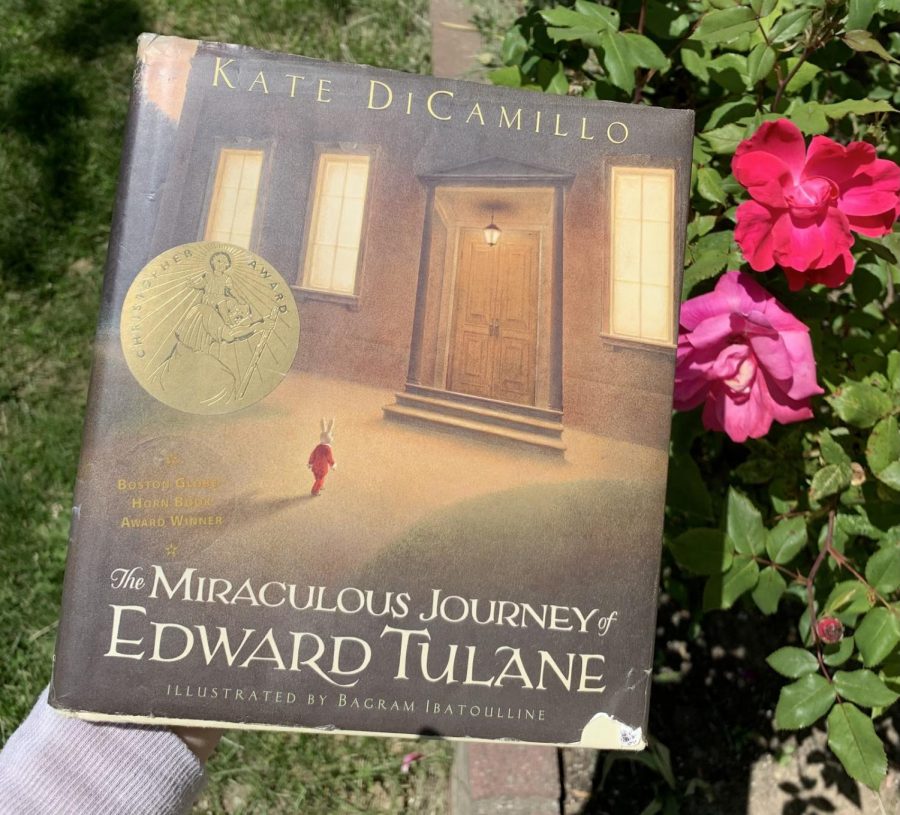

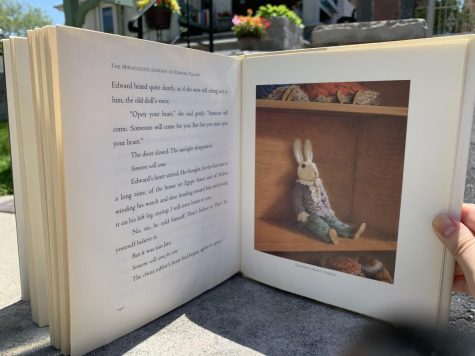

Here is a worn copy of “The Miraculous Adventures of Edward Tulane” with its tattered corners, passed down from my cousin who had read it years prior.

Kate DiCamillo. The name rings familiar in the minds of many elementary school graduates and even those who are still in their primary grade school years. Her name is printed across various books, sprinkled throughout the classroom library, in an iconic Garamond Ludlow font.

I was first introduced to DiCamillo in the third grade. My teacher had just announced our new guided reading book for the next three months and distributed the newly-printed copies. Like any child, I was excited to be trusted with a new gift and immediately took ownership of the novel. It was Kate DiCamillo’s Newbery award-winning book Because of Winn-Dixie.

I had initial doubts. How interesting would a story about the neighborhood adventures of a 10-year-old girl and her robust dog possibly be? The answer was “Very!”

At the time, I only read fantasy novels by Joan Holub, Suzanne Williams’ Goddess Girls, Coco Simon’s teenage high school drama series titled Cupcake Diaries, and the comedic, lively illustrated Geronimo Stilton series by Elisabetta Dami. However, I was pleasantly astonished by the slice-of-life narrative, which was vastly different from the books I was borrowing at the time.

At first glance, DiCamillo’s novels seem appealing to children in the same way that other widely successful series such as Percy Jackson and Harry Potter appeals to them. However, DiCamillo has a remarkable ability to treat kids as intelligent readers and does not hesitate to challenge them with advanced themes and vocabulary. Even better, she does nottry to clear up the sad notes left at the end of her novels. While it was hard to swallow as a kid, her open endings are more realistic which invites the reader to think for herself.

DiCamillo’s work focuses mainly on animal protagonists as in her Newbery Medal-winning books The Tale of Despereaux and Flora & Ulysses. While her novels are directed towards children, they welcome readers of all ages, exploring many themes that adults still have a hard time comprehending. It is refreshing that she does not underestimate a child’s ability to comprehend feelings of love, hope, loss, and transformation. These emotions are universal and will be seen time and time again throughout one’s life. Understanding them at an early age is key, and DiCamillo starts the conversation by inviting children to sit at the table. Her novels are a tool that connects us with the difficulty of being human. While books like the Harry Potter series offer tales of adventure for children, DiCamillo’s stories provide more of a spiritual journey.

A few weeks ago, I did some spring bookshelf cleaning, due to the unrelenting nagging of my mom, when I found my old copy of the 2006 The Miraculous Adventures of Edward Tulane. It had been a long time since I had last read it, and I had almost forgotten completely that I actually owned it. Nonetheless, the book was still familiar to me. It slid out of its detachable cover, mimicking the color scheme of a warm old lamp that was darkened by time.

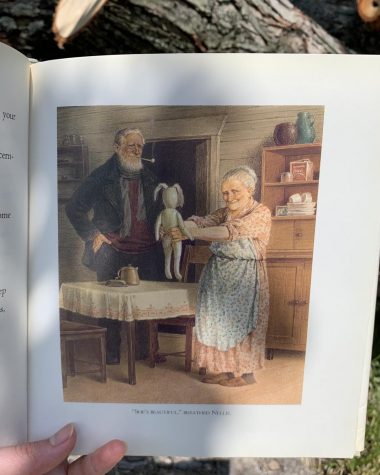

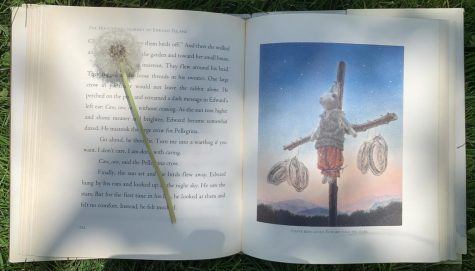

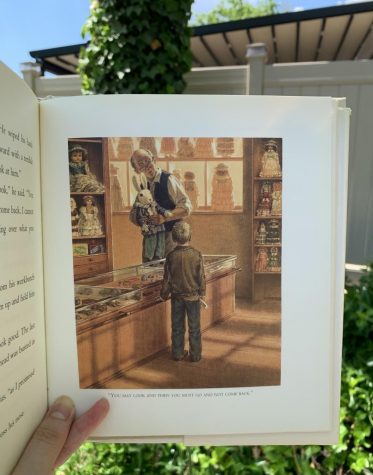

The yellow-green hardcover book felt heavy, and it had an imprint of a pocket watch engraved on the outside, a consistent symbol throughout the novel. On the creme-colored papers lay spare but moving words and unforgettable images by illustrator Bagram Ibatoulline. Each illustration conveys the same warmth as the artwork on the dust cover and brings the story to life. The novel has the comfortable feeling of a storybook.

Even several years later, the plot remained vivid in my memories. It told the tale of Edward Tulane, an expensive rabbit doll who was incapable of loving anyone, despite having an owner, Abilene, who loved him dearly. Her grandmother, Pellegrina, tells a cautionary tale the night before Edward is separated from Abilene about a beautiful princess who suffers a grotesque fate due to her selfishness and vanity. Her mindset mirrors that of Edward’s, and the parable warns him about the consequences of his continued cold-heartedness.

As the story continues, Edward leads many lives and takes on many names. He’s passed from the hands of a fishing couple to a migrant worker and his dog, and most memorably, to the hands of a little girl with tuberculosis. Just as the reader gets comfortable with Edward’s current owner and lifestyle, she is suddenly ripped from it. As DiCamillo writes, “How many times…would he have to leave without getting the chance to say goodbye?” Although it is necessary for him to broaden his perspective, we, like Edward, cannot help but feel like there is no place for him, until he evidently finds a new home, only to be taken again. The story is a constant cycle of loss and transformation. With each change of hands, Edward learns how to love. Just as he thinks he is broken down and unable to love again, his heart opens wider with seemingly unlimited space.

It is exhilarating to see his progression. Edward is an anti-hero who is selfish, vain, and hollow. However, as he experiences life’s full spectrum of wealth, poverty, moments of happiness, and grief, he becomes a better listener and his appearance becomes increasingly insignificant. He becomes grateful for every glance that he gets of the night sky after being trapped under piles of garbage and stranded in the murky black depths of the seafloor. As children, we have few chances to meet an extremely flawed character such as Edward, yet witness truly profound character development at the same time.

When I first read the book, I understood that Edward’s journey was about self-discovery and love, but I did not grasp the complexity of this concept. Even now, it is hard to express, but one quote from this wise century-old doll stuck out to me: “If you have no intention of loving or being loved, then the whole journey is useless… Someone will come for you. But first, you must open your heart.” Love and separation go hand-in-hand. We must not be afraid to love even if it is only temporary.

At the end of the story, Edward is reunited with the grown-up Abilene and her daughter, Wendy-Peter-Pan-style. The story is as much internal as it is about his distant travels. Through the repetition of loss and love, DiCamillo tells a miraculous story indeed.

“How many times…would he have to leave without getting the chance to say goodbye?”

Nicole Zhou is the Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Observatory' yearbook and a Staff Reporter for 'The Science Survey' newspaper. This is her third year revising...