The History and Culture of Mahjong

From contraband to community builder, how did Mahjong become one of the most beloved games in Chinese and Jewish communities?

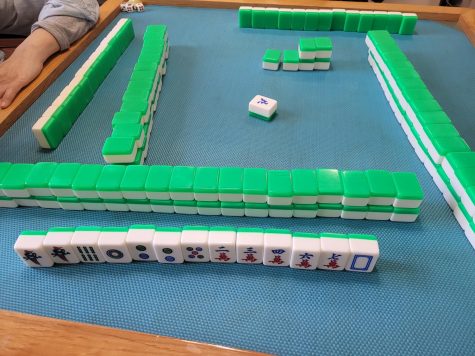

Here is an up close image of Mahjong tiles.

Four players huddle around the square wooden table. Each takes turns grabbing and discarding tiles from the diamond-shaped Mahjong tile stack. Onlookers stand and peer over the shoulders of the competitors. And in an instant, one of the players grabs a tile, peers at it, and yells out “食糊” (Sik Wu) in Cantonese, flipping over their row of tiles in one swift motion as their opponents groan in defeat.

Growing up in a Chinese American household, this was a common sight to behold at family gatherings, parties, and celebrations. As a child, I remember the adults sitting around the square mahjong tables for hours. I would peek over the shoulders of my dad, perplexed at how this complex game worked. To an 8-year-old, these mahjong tiles looked like nothing more than glorified building blocks that my brother and I would use to build towers when the adults stepped away from the table to eat. I always assumed that mahjong was an ancient game that emperors of the Tang and Song dynasties once played. “The symbols on Mahjong pieces always fascinated me whenever I saw my grandparents playing. The rules always seem so complicated, as I built towers while they played,” said Justine Chen ’21. But the game is actually much younger than most people would think.

As we know it today, the history of mahjong dates back to the mid-1800s in Southern China towards the end of the last imperial dynasty, the Qing Dynasty. The game rose to popularity during a time of adversity in China when tragedies were striking left and right. Through China’s defeat in the first opium war — the Taiping Rebellion — and the fall of the Qing Dynasty, Mahjong spread like wildfire through the treaty ports that were opened due to the unfair Treaty of Nanking.

People from all over China traveling through the ports would bring the game back to their respective provinces, and before long, the game was being played by wealthy, poor, men, and women alike, all over the country. But like its predecessor Madiao, the game received heavy criticism from scholar-officials as signs of moral decay, corrupt officials, and wasting time.

Madiao was an extremely popular tile game towards the end of the Ming Dynasty. As a result of this popularity, the game came to be associated with the fall of the dynasty. Madiao was likely modified and combined with other types of games to create the Mahjong people play today. Many speculate that the images adorned by mahjong tiles took inspiration from Madiao. Over time, mahjong grew to be associated with the more corrupt parts of society and was even banned in 1949 by the People’s Republic of China.

But even amid the negative connotation that the game held, Mahjong still had a firm hold on the hearts of the people. During the 1940s, many women would escape from the harsh realities of their daily lives by gathering with their Mahjong friends. It was during this era that the leftist intellectual Wu Han would host discussions regarding politics and current events under the guise of playing Mahjong while he was under surveillance by China’s nationalist security forces. This worked well as Mahjong is a noisy game. Shuffling hard tiles creates loud rumbling and clacking noises, perfect for covering up conversations. It was not until 1985 that the game was brought back and began to prosper again.

While the game was a hit in China, it also became relatively popular internationally in countries like America and Japan. Entrepreneurs and tourists visiting China brought the game over to the United States, where it became a fad during the 1920s. The game became crucial to facilitating a sense of community in groups such as Chinese American immigrants and Jewish American women. In the 1920s and 1930s, Chinese Americans who were labeled as perpetual foreigners by other Americans found the sense of community they were searching for in Mahjong. While the Mahjong craze started dying out for many Americans after the 1920s, in 1937, the National Mah Jongg League was formed in an attempt to standardize the rules of the game and help revitalize the game.

Almost all the people that helped form the National Mah Jongg League were Jewish American women. Consequently, these women spread the game to other members of the Jewish communities that they were in, causing mahjong to be a game deeply ingrained in the culture of many Jewish families to this day. Many of the younger generations of Jewish American descendants are revisiting the game to connect with their heritage and rekindle fond memories of their parents. After World War II, Mahjong was especially important to Jewish American women who had moved to suburban areas from cities. Mahjong became a way for these women to build social connections in these new neighborhoods. Some of these women held positions as leaders, entrepreneurs, and game smiths, and largely contributed to the growth of American Mahjong which differs slightly from the Chinese mahjong. Even then, the game varies between different provinces in China as each province has their own name for the game in their regional dialects and variations on the rules. Variations of the name include ma ch’iau, ma cheuk, and ma jiang.

Today, Mahjong is still a prominent part of Chinese and Chinese American culture. Not only is the game a source of entertainment at gatherings, but it is a very important part of the lives of many Chinese elderly. In both China and America, Mahjong allows elderly a way to socialize, eliminate boredom, and promote cognitive activity. Mahjong has also worked its way into pop culture in movies such as Crazy Rich Asians.

Whether playing Mahjong is a way to reconnect with our heritage or simply connect with others, it is an inherently social game that brings people together. Mahjong has persisted through the decades, the centuries, and the falling of dynasties, and the game will continue to build communities for generations to come.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Chinese Americans who were labeled as perpetual foreigners by other Americans found the sense of community they were searching for in Mahjong.

Rachel Koon is the Features Section Editor of 'The Science Survey' where she provides feedback to Staff Reporters writing articles for this section. She...