Epic Satire: The Story of Discworld

How one of fantasy’s most prolific authors built a world that managed to satirize everything about the genre, even itself.

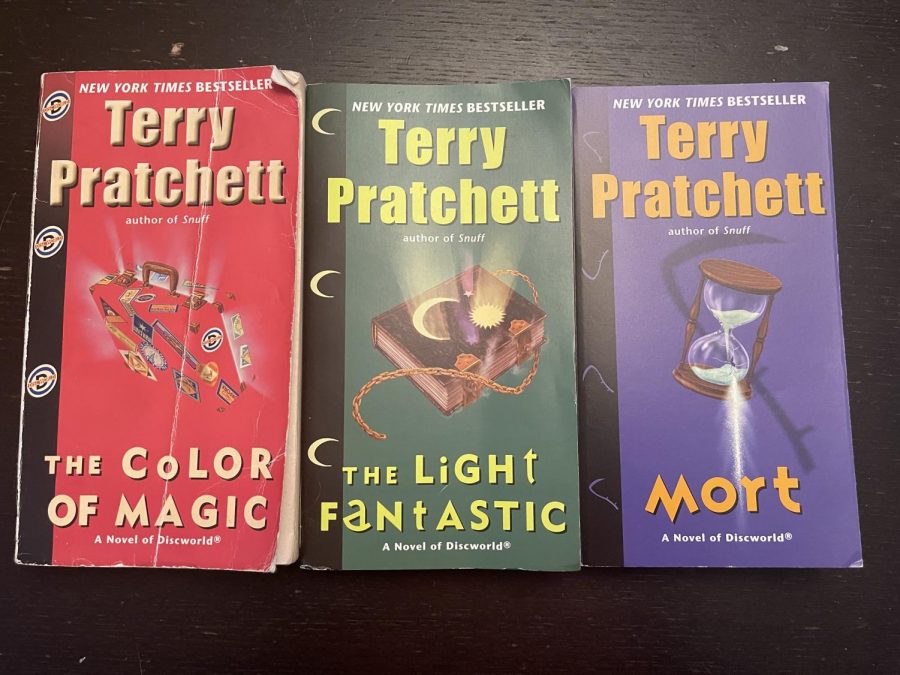

Here is a selection of popular Discworld books by Terry Pratchett.

Tolkein’s shadow reaches far over the fantasy genre. His works have defined the landscape since their publication, and it is rare to find a book that fully escapes one of the tropes or cliches he popularized. Tolkein’s toolkit is robust, but his works set such a high standard that many books suffer while attempting to emulate the structure and style of his works.

Many great fantasy novels of this century and the last use Tolkein as inspiration, but change the formula and world-building enough to create wonderfully unique worlds populated with interesting characters. However, the fact stands that many of these books succeed not because of their proximity to The Lord of Rings, but in spite of it, and for years the world lacked a series that embraced or even parodied cliches and tropes in fantasy.

In 1983, then-journalist Terry Pratchett published The Colour of Magic, a little fantasy anthology of strange stories set in the Discworld, a large disc flying through space on the back of four giant elephants that themselves are riding on the back of a giant cosmic turtle named A’Tuin. The Discworld presents itself as an interesting, serious setting where one can expect to see traditional fantasy adventures. Upon closer inspection, however, readers find that every aspect of the Discworld as presented in The Colour of Magic has been carefully constructed for the sole purpose of parody.

(Otho Valentino Sella)

This satire begins with the protagonists of The Colour of Magic, who go on to star in multiple Discworld books after their debut. Rincewind is the star of the show, and takes the knowledgeable wizard trope and flips it on its head, instead being characterized as a serendipitous coward who dropped out of wizard school and only knows one spell. He is tasked with being a tour guide for an immensely wealthy tourist named Twoflower and his magical toothed luggage. Together these characters stumble their way through various strange situations, each connected by an emaciated plot structure overflowing with as much satire as can possibly be packed into 277 pages.

The Colour of Magic is unique even among Discworld books, in that it almost completely forgoes a traditional plot in favor of a series of one-off gags. Locations are mentioned for the purpose of a joke and then never reappear, characters spend dozens of pages as the focal point of the story only to be stabbed for the sake of a punchline, and the entire world gets rewritten briefly by powerful magic, threatening to render the entire story irrelevant.

One may expect the sheer density of these strange, comical moments would make the plot of The Colour of Magic to become concave, forgettable, and empty, but the jokes themselves manage to hold the book together. However, the story does not suffer so, and I finished the book remembering one key plot point that mapped out the course of the now 40 book long Discworld series, with the final book being published in 2015.

At the end of the final story included in The Colour of Magic, Rincewind and Twoflower fall off the edge of the Discworld, leaving the reader with a literal cliffhanger. The sequel, The Light Fantastic begins to change up the formula. It picks up where The Colour of Magic left off, but has a far more coherent plot, revolving around Rincewind’s limited magical abilities and a prophecy about the destruction of the Discworld.

The more coherent plot does not mean that the tone of The Light Fantastic is different from its predecessor. Jokes and parody still run rampant, but they take a backseat so that the story itself can flourish. That said, the books still place large emphasis on jokes, and many opportunities for depth of character and theme remain unexplored.

After The Light Fantastic, Terry Pratchett continued publishing books, and as he did so, something interesting began to happen to the Discworld — it began to get more serious. More sub-series began to be added, slowly filling out the world and locales that had previously only existed to land a punchline. Eventually, Discworld books went from a parody of fantasy, to simply funny fantasy; they became romps through an interesting world with surprisingly emotional and well-developed characters at their core.

Pratchett even made a foray into the world of young adult novels, with a personal favorite of mine, The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents, which tells the charming story of a cat and some mice that magically gain human-like intelligence and begin going from town to town running a pied-piper-esque scam. The book has funny moments and joke characters, sure, but at its core are interesting questions about the responsibility that comes with intelligence, and strong themes about acceptance and friendship.

This era of Discworld is known as The Golden Age, and it contains wonderful books like Guards! Guards!, which tells the story of the city guards in Ankh-Morpork, the Discworld capital, and their fight against a dragon that suddenly appeared and took over the town. The main characters of this book rise to challenge the jokes and tropes they are meant to be parodying, rather than simply embodying them, and manage to become as interesting as the world they inhabit.

The Discworld started out unmapped. Terry Pratchett famously claimed that, “You can’t map a sense of humor.” However, over 3 decades and 41 novels, he managed to not only map that sense of humor, but evolve it into something truly worthy of being called iconic.

“Satire can definitely be art” said Alice Lin ’22. “It’s a form of expression that can convey important messages while possibly getting a few laughs from the audience.”

Otho Valentino Sella is an Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey.' Otho has always been fascinated by stories and storytelling, and he sees journalistic...