The Printing Press and Planetary Conquest: A Brief History of Science Fiction

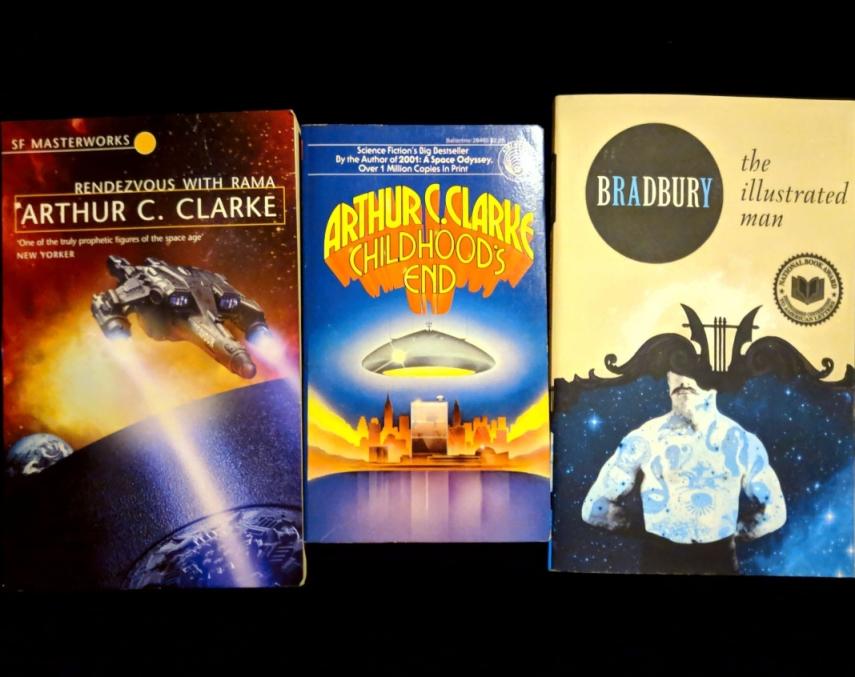

From left to right, three of my favorite science fiction books that I own are ‘Rendezvous with Rama’ and ‘Childhood’s End’ by Arthur C. Clarke, and ‘The Illustrated Man’ by Ray Bradbury, which is a collection of his short stories.

Pigs aren’t really able to bend their necks upwards. A pig, standing up, just cannot look into the sky. They have to roll onto their backs to see it. It is a cool fact that I think is worth noting because our ability to look at the sky has shaped all of us. It is human nature to gaze up at the stars and wonder what is out there. The spirit within us that makes us wonder what lies beyond is the same spirit that drives humanity to do incredible and sometimes terrible things. That sentiment is a big part of science fiction, a relatively young genre but potentially one of the most important.

Science fiction is fairly nebulous and hard to define. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as “fiction in which the setting and story feature hypothetical scientific or technological advances, the existence of alien life, space or time travel, etc., especially such fiction set in the future, or an imagined alternative universe.” There are many stories that are easy to positively refer to as science fiction, but there are many more that are unclear. I personally even have trouble calling Star Wars a work of science fiction. This makes eras of science fiction difficult to precisely define, meaning that the complete history and ramifications of the genre are impossible to discuss in a single article.

While many ancient stories contain elements of science fiction, such as One Thousand and One Nights/Arabian Nights from the Islamic Golden Age, it’s difficult to say that any early works were the first science fiction story. Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift from 1726 contains some sci-fi-like elements, such as the floating city of Laputa. There are some other notable works from the Enlightenment period that one could call precursors to sci-fi, as the time period was marked by a greater focus on science, reason, and philosophy.

What many consider the first work of science fiction is Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein. It tackled what it means to be human, early forms of artificial intelligence, and it arguably created the “mad scientist” trope. Another Mary Shelley novel from 1826, The Last Man, is a very strong contender for a title as one of the first science fiction novels, taking place in a 21st-century dystopia. There are two other 19th-century authors which have to be mentioned: Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. Verne wrote wildly adventurous stories framed around technology with varying degrees of advancement, like his 1869 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Wells’s stories were much less focused on the specifications of the technology, rather using them as plot devices to justify more introspective or speculative stories about human society. No, his 1895 novel The Time Machine is not an instruction manual.

Scientific advancements became increasingly relevant to Americans in the 1920s and 1930s — things like planes, cars, and medical technology. Science fiction started developing more, but at this point, it was still largely intertwined with other genres, like fantasy. H.P. Lovecraft also used elements of science fiction in his horror stories to create cosmic horror. This era is responsible for the massive rise of science fiction in pulp magazines. These were considered still a low form of art, and many of these stories that helped to popularize the genre were about action and adventure, laser guns and martians. Nelson Dong ’21 said that science fiction stories of this nature are “cool but unrealistic,” and that a lot of the favorite technology of sci-fi stories, such as flying cars, are not likely to appear at any point in the foreseeable future.

For the time period, this makes a lot of sense. In the 1930s, a lot of popular science fiction had an optimistic view of the future because people wanted an escape from the hard times of the Great Depression and rising global tensions. Evan Rothstein ’21 said that that escape from reality is “part of what makes science fiction so important.” Another very important development of this era was film — these stories were being told on the silver screen, and it was in the late 1920s that movies with sound started being made. In these two decades, three Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde movies were made (two in 1920 and one in 1931), and one of the greatest sci-fi movies of all time came out in 1927 — Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

The 1940s and 1950s are often called the Golden Age of Science Fiction. The rise of science fiction as an art form can be attributed in large part to John W. Campbell, Jr., the editor of the Astounding Stories of Super-Science magazine. He shaped the works of many very notable writers like Isaac Asimov. This Golden Age was paralleled with a rise in realism in science fiction from people like Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and Arthur C. Clarke. They are considered the “Big Three” writers of the genre. At this point, science fiction began to really boom, and it is impossible to address all the things that arose during this time and in subsequent decades.

The Golden Age bled into the 1960s and 1970s when the existential peril of the Cold War and the prospect of nuclear attack started to take over. The late ’50s and onward saw a trend of pessimistic disillusionment in many sci-fi stories, a stark contrast to the sometimes pulpy optimism of the ’20s and ’30s. By that point, the shift from stories about green men on the moon to stories about the nature of human society was apparent. Star Trek and The Twilight Zone, two of the greatest shows ever, popped up around this time. Their episodes were often thoughtful and poignant. One of my personal favorites that I think is worth mentioning is the 1961 The Twilight Zone episode ‘The Shelter.’ I do not want to reveal too many details, but in the episode, a few friends are having dinner in a quaint suburb when an announcement is made that a nuclear attack may be imminent. The rest of the episode follows what they do when they hear this news. It is an amazing episode, and I would recommend it to everyone.

Each shift in technology since then has inspired countless stories that discuss human nature through the lens of technical innovation. Since the Golden Age, popular diversity in science fiction has increased, though maybe not enough. Stories in the genre have always tackled themes of dehumanization, coexistence, and societal reactions to things that we see as the “other.” We do not often think about it, and though they are often intergalactic, so many stories have been written about colonization. Many classic tales envision a post-race world where humanity is completely united, but the expansion of the genre has allowed for more nuanced commentaries to gain recognition. The late 20th-century witnessed the birth of cyberpunk, which took a high-tech aesthetic, recognized existing socioeconomic inequalities and extrapolated what that means for humanity.

A genre so focused on the future cannot be restricted to the failures of the past. One of the greatest modern science fiction writers was Octavia E. Butler, whose stories portrayed black women in leading roles and put a feminist lens to the science fiction genre. Another widely revered science fiction great is four-time Nebula Award winner Samuel Delany. It should be noted that Delany graduated from Bronx Science in 1960 and is a member of the Bronx Science Alumni Hall of Fame. He has published multiple novels parallel to the Civil Rights movement, and many works of his explore themes of sexuality. According to his website, he was “chosen by the Lambda Literary Report as one of the 50 people who had done the most to change our view of gayness in the last half-century,” and he was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2002.

The 21st-century has seen the continued progression of science fiction. Many old properties are being re-contextualized and reinterpreted. In 2016, Matt Ruff published Lovecraft Country which paired Lovecraftian horror with the systematic racism of the Jim Crow era. This is particularly powerful because, while Lovecraft wrote some great stories, he was an incredibly racist, xenophobic, and hateful man. He was not a good person, and that bled into his stories which often demonized immigrants and people of color. That updated take has been turned into an HBO show this year. Another notable revival is the 2019 The Twilight Zone reboot headed by Jordan Peele, who has had a very successful career and is one of the most visionary directors working today. The internet has allowed for many new voices to come into the picture, broadening the scope of science fiction and giving it a brighter future.

Sci-fi is one of the most important genres because it combines the potential of humanity to create with the potential of humanity to destroy. People always want to know about the future. They want to either fear it or be excited about it. As long as we have hope for the future, science fiction will persist. If the hope for a future goes away, the genre will probably be over. I think that the role of sci-fi is best summed up in a quote from 1968 by author Frederik Pohl, referring to something Asimov first described: “a good science-fiction story should be able to predict not only the automobile but the traffic jam.”

“A good science-fiction story should be able to predict not only the automobile but the traffic jam,” said author Frederik Phol.

Kellen Knight is an Editorial Editor for 'The Science Survey.' He likes the capacity of journalistic writing to disseminate information efficiently and...