‘Like Life’: Where Art Meets Anatomy

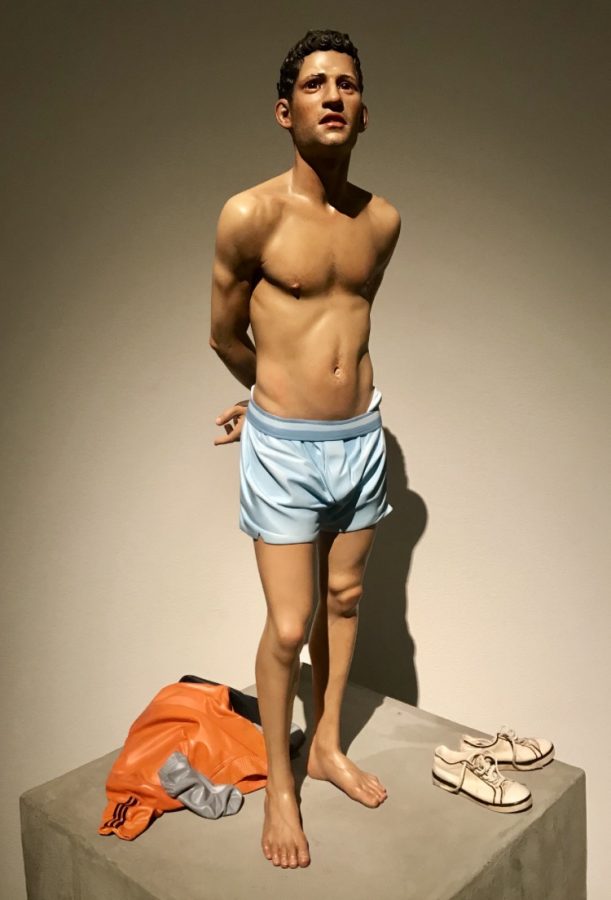

‘Action 105: An Israeli soldier points his gun at the Palestinian youth asked to strip down as he stands at a military checkpoint along the separation barrier at the entrance of Bethlehem,’ 2006.

Mannequins and reliquaries and wax effigies, oh my! From Louise Bourgeois to Donatello to Méret Oppenheim to Edgar Degas, ‘Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and The Body (1300–Now),’ currently at the Met Breuer, explores the complexity of the human body in the form of 120 drastically different works of art created during drastically different periods by drastically different artists. From European sculpture to contemporary art, each piece is united by the exploration of life versus art, original versus copy, and the age old adage of “does art imitate life or does life imitate art?”

For much of Western history, sculpture favored idealized and heroic white marble prototypes. ‘Like Life’ juxtaposes these traditional sculptures with nontraditional ones to invite conversation, to make viewers wonder just how accurate figurative sculpture should be when it comes to resembling the body.

‘The Mete of the Muse’ by Fred Wilson, for example, places the goddesses Nephthys and Aphrodite side by side. The figures are obvious contrasts, both in terms of style and of the material used. The “mete” of the two figures transcends figurative pleasure and allows the viewer to ponder the cultural and aesthetic boundaries from which these two works of art originate.

The prevalent regard for displays of nudity was not as easily accepted in nineteenth century as it is now. In fact, when ‘The Tinted Venus’ by John Gibson was unveiled at the 1862 International Exhibition in London, it was met with horror. With her wax-tinted flesh and gilded accessories, this sculpture astonished viewers who were accustomed to the haughty, colorless marble statues that adorned Rome. ‘The Tinted Venus’ was shocking to audience members who subsequently deemed it “a naked, impudent Englishwoman.”

In the same vein, ‘Hercules’ by Willem Danielsz van Tetrode was criticized upon its unveiling because the artist chose to depict Hercules as a man rather than a demigod, stripped of his signature lion skin, with slightly sunburned shoulders, and a body worn with age.

This conflict concerning when the line between acceptable nudity and indecency is crossed is not just restricted to the world of art. ‘Miller v. California,’ a significant Supreme Court decision, attempted to draw such a line by establishing the “Miller Test.” In particular, whether the sale and distribution of obscene materials is protected under the First Amendment.

“That’s so creepy,” remarked one guest as she peered into the eyes of ‘Jeremy Bentham’ by Thomas Southwood Smith.

In history, the most common way to imitate skin and flesh is the application of color. However, in ‘Like Life,’ artists created casts from real bodies, constructed movable limbs, dressed sculptured models in clothing, and even incorporated human body parts (teeth, bones, blood, and hair) into their work. The uncanny resemblance is meant not only to alarm and excite, but also to cause the viewer to reevaluate himself, those around him, and his place in society.

“That’s so creepy,” remarked one guest as she peered into the eyes of ‘Jeremy Bentham’ by Thomas Southwood Smith. Jeremy Bentham was a Utilitarian philosopher who specified in his will that his body be dissected in the name of science, but also preserved so that he could “attend” meetings with his devoted disciples. This “auto-icon” contains Bentham’s skeleton and therefore literally embodies the sitter.

Perhaps slightly more obvious, Marc Quinn’s “self-sculpture” is a mold of the artist’s face, filled with ten pints of the artists blood. Promptly titled ‘Self,’ it lacked an artistic component and relied on its gross, unnerving, and unconventional material to entice viewers.

On the other hand, the ‘Reliquary Bust of Saint Juliana’ managed to perfectly balance the artistic and eccentric, resulting in a hauntingly beautiful piece. Saint Juliana, born in 285, was tortured and beheaded at the age of eighteen after she refused to marry a pagan. In 1376, Abbess Gabriella Bontempi obtained a skull fragment of Juliana from her convent in Perugia and placed it in a head-shaped reliquary case. The softness of the face and the fact that it contains an actual body part serves as a powerful symbol and an eerie presence.

‘Like Life’ also examines the complexities of the human body in relation to religion — which has often quarreled with the use of iconography. ‘The Idolatry of Solomon’ by Lucas Cranach the Younger illustrates this quarrel — particularly, in relation to Protestants during the sixteenth century, who condemned and destroyed sacred images. Images they believed could be improperly coveted for their beauty and lead people to stray from their religious devotion. Cranach’s painting was created during the Protestant Reformation and illustrates a story from the Old Testament in which King Solomon worships an exotic pagan idol. The painting was meant to stress the cautionary tale of idolatry and the ability of women to “distract, seduce, and beguile even the most holy of men.”

‘Pygmalion and Galatea’ by Jean-Léon Gérôme was inspired by Ovid’s myth of a sculptor (Pygmalion) so consumed with desire for his statue of Venus that she comes to life. The painting shows the exact moment of transformation, when Galatea’s body turns from stone to flesh. This idea of art, specifically sculpture, transcending into real life, has often plagued religion.

Since the dawn of religion, iconography like images of Christ on the cross have been used to frighten or inspire viewers into submission. But when the likeness of the work caused the subjects to crave the human form and not God, it was promptly discarded.

‘Like Life’ highlights both the pleasures and anxieties of the human body, which is especially relevant in an increasingly image-conscious world. Love it or hate it, ‘Like Life’ invites heated discussion, causes shrieks of alarm, and provokes contemplative musings.

‘Reliquary Bust of Saint Juliana,’ circa 1376.

‘The Idolatry of Solomon,’ circa 1537.

‘Auto-Icon of Jeremy Bentham,’ 1832.

‘The Housewife,’ from 1969-1970.

Oona Zlamany is a Managing Editor of ‘The Science Survey’ and a Student Life Reporter for ‘The Observatory.’ Oona believes that journalism is essential...