Michelangelo: The Superhero of the Year

The largest Michelangelo exhibition in history — and truly, the art show of the season— was “Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer,” recently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which displayed 200 works (including 133 drawings) of one of the greatest artists of all time.

Michelangelo, an Italian born in 1475, embodies the term Renaissance man (an individual well versed in many fields) and has left an amazing legacy that few can compare to: an entire body of work that encompasses sculptures, painting, architecture, and poetry. Michelangelo contributed to the humanity of art through his desire to glorify the human form. All of his creations—the David, the figure of God in the Sistine Chapel, and the Pieta—bulge with defined curves and musculature. Michelangelo spurred the movement of the Italian Renaissance, where mankind were the model of ideals, rather than the underlying form of the gods. Michelangelo depicted man as the greatest creation of God: heroic, taught, and muscular.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian,

Caprese 1475–1564 Rome)

Portrait of Andrea Quaratesi

1532

Drawing, black chalk; 16 3/16 x 11 1⁄2 in. (41.1 x 29.2 cm)

The British Museum, London

Michelangelo achieved great fame in his lifetime and as a result, his career is extremely well documented. Michelangelo was the first western artist to have a biography published in his lifetime.

In fact, Michelangelo was so popular when he was alive that two rival biographies were published at the same time. Even though Michelangelo liked to pretend that he was untrained, he was an apprentice at the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio as early as thirteen. Historians speculate that he learned to make “blueprint” drawings before moving on to more solid mediums. These methods, though common now, were unusual during his time. Lucky for us, the drawings, which made up the majority of the show at the Metropolitan Museum, are a spectacular feat. It is remarkable to think that Michelangelo created them when he was only seventeen.

Michelangelo’s talent did not end on paper; he was also very skilled with stone. The most notable sculpture in the Met exhibit, entitled the ‘Young Archer,’ has undergone much scrutiny. In 1996, the sculpture was identified as a Michelangelo, but only after years of obscurity in the French Embassy on Fifth Avenue. While historians continue to debate the authenticity, those who believe that the sculpture is a Michelangelo (the Met included) believe it would have been produced between 1496 and 1497, when Michelangelo was only twenty-one.

The beauty of the Michelangelo show was that it allowed the viewers to see how Michelangelo went from point A to point B, from paper to canvas, from pencil to paint. Viewers could understand where the art came from. It almost felt like you had been let in on a secret by the very man himself, as if Michelangelo had floated down from the heavens and shown you the hidden world behind his magic. The fact that the drawings lacked paint only allows you to appreciate the texture even more.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian,

Caprese 1475–1564 Rome)

Portrait of Andrea Quaratesi

1532

Drawing, black chalk; 16 3/16 x 11 1⁄2 in. (41.1 x 29.2 cm)

The British Museum, London

This show was both time and light sensitive. The drawings are very fragile, so they can only be exposed to light for a maximum three-month period. The drawings, which were done in red chalk, black chalk, or brown ink, depict many a male nude in states of motion. The drawings depict male figures raising an arm, twisting at the waist, or balancing on one foot. Michelangelo’s subjects range from religious tales (such as the resurrection of Jesus Christ) to classical ones (such as Hercules wrestling the fabled lion).

The figures’ expressive postures and curvy silhouettes differ from the standard medieval figures which resembled wooden dolls with rigid postures. Michelangelo’s figures feel alive and tangible; they could almost jump off of the page.

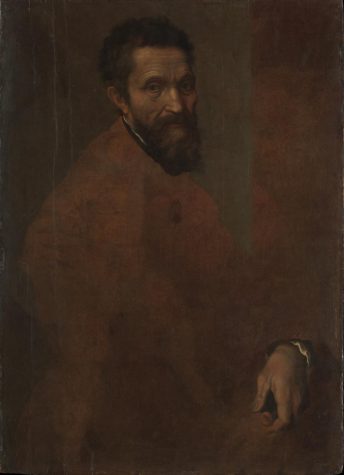

Daniele da Volterra (Daniele Ricciarelli) (Italian, Volterra 1509–1566 Rome)

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564)

Probably ca. 1544

Oil on wood

34 3/4 x 25 1/4 in. (88.3 x 64.1 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Clarence Dillon, 1977

1977.384.1

The final, almost theatrical, and most thrilling part of the show was the mock Sistine Chapel. A lit-up, moving screen (attached to the ceiling) with images of the iconic motif added to the surreal nature of the scene. The cherry on top: wooden scaffolding. It was positioned strategically, almost to suggest that Michelangelo is merely on a coffee break and will soon be back, on his back, painting his masterpiece.

This is one of those shows that one might look back on years from now and think, “I was there,” because it is very unlikely that a Michelangelo show of this magnitude will be assembled within your lifetime. Keep that in mind the next time you find yourself aimlessly watching T.V. or playing video games, because you are truly missing out.

Oona Zlamany is a Managing Editor of ‘The Science Survey’ and a Student Life Reporter for ‘The Observatory.’ Oona believes that journalism is essential...