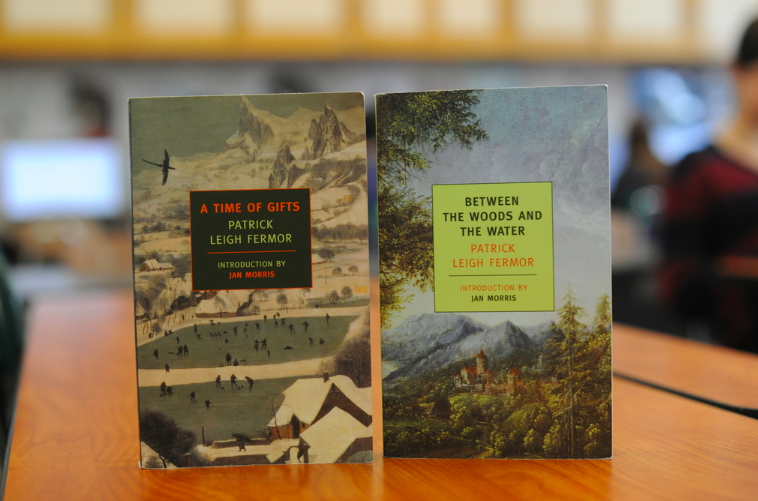

Patrick Leigh Fermor’s European Odyssey: A Review of ‘A Time of Gifts,’ ‘Between the Woods and the Water,’ and ‘The Broken Road’

In 1933, a nineteen-year-old Fermor abandoned school and explored Europe, first landing in Holland and then walking all the way to Constantinople, chronicling his adventures in the travel journals which would later provide the blueprint for his literary masterpieces: ‘A Time of Gifts’ and ‘Between the Woods and the Water’. A third volume, ‘The Broken Road,’ was published posthumously.

Jan Morris, in her introduction to the New York Review of Books edition of ‘A Time of Gifts,’ published in 2005, describes the book as “a work of genius.”

On a European odyssey, a 19-year-old Patrick Leigh Fermor breaks bread with peasants, sleeps placidly under a canopy of weeping willows, explores majestic libraries and fairytale woods, loses a blooming love during a few enchanting Transylvanian months, and befriends a spectrum of strangers ranging from counts to gypsies. Leaving behind only footprints but forever carrying an undying spirit of adventure, Fermor proves the value of invariably breaching the bounds of one’s comfort zone and perpetually pursuing the open road ahead.

Destined to explore, Fermor did not fit the mold of his austere British boarding school. In his third year, his housemaster wrote that Fermor was “a dangerous mixture of sophistication and recklessness which makes one anxious about his influence on other boys.” After a string of minor misdemeanors, a scandalous incident terminated his turbulent schooldays; he was “caught red-handed,” holding a girl’s hand in the local village and thus inadvertently liberated himself from the rigidity of British academia in the ultimate act of defiance.

After a brief stint in the army, Fermor, driven by his instinctive impulse for adventure, vowed to “abandon London and England and set out across Europe like a tramp.” He writes that “All of a sudden this was not merely the obvious, but the only thing to do. I would travel on foot, sleep in hayricks in summer, shelter in barns when it was raining and snowing and only consort with peasants and tramps.” Thus, he packed the bare necessities (a volume of Horace and a selection of blank notebooks), excitedly poured over travel plans with his eager mother, and set foot in 1933.

Driven by the goal of reaching Constantinople, Fermor ventures through Europe. A truly lovable, intelligent, and chivalrous Englishman, Fermor takes the road less traveled and jots down a plethora of notes along the way, recounting his gleeful times with Annie and Lise (two wealthy, young German hostesses), his reflections on the majestic European countryside, and his ponderings on the medieval spirit of the Danube School paintings. As Fermor weaves his words together, he forms a brilliant tapestry of thought, eliciting a sense of breathless wonder and granting readers a treasured glimpse into the galvanizing powers of youth.

This noble mission marked the genesis of two literary masterpieces compiled decades after a three-year long journey through the heart of Europe. After piecing together old journal entries, Fermor published A Time of Gifts in 1977 and in 1986, he released Between the Woods and the Water, both republished in handsome paperback editions by New York Review of Books. While often reduced to the simplistic title of ‘travel memoirs,’ these books provide a striking intersection between Fermor’s young, innocent naivete, his erudite reflective capabilities, and his golden literary touch. Utterly captivating, these sensational works contain cross-references and comic relief, foreshadowing and fun, and allusions, afterthoughts and astounding anecdotes.

In A Time of Gifts, Fermor first lands on the Hook of Holland. Brimming with an energizing sense of exultation, he describes his first glimpse of Europe: “Snow covered everything and the flakes blew in a slant across the cones of the lamps and confused the glowing discs that spaced out the untrodden quay… I was still the only passenger in the train and this solitary entry, under cover of night and hushed by snow, completed the illusion that I was slipping into Rotterdam, and into Europe, through a secret door.”

In Holland, Fermor’s love of nature and novelty shine through. He frequently expresses his wonder at the “clear beauty of the country” and “the sway of its healing and collusive charm.” Moreover, he notes that his interactions with the Dutch left him with “a deposit of liking and admiration which has lasted ever since.” Transcending language barriers and national boundaries, Fermor cements his position as a global citizen and illustrates the importance of the threads of commonality which enigmatically link people separated across diverse walks of life.

Following his adventures in Holland, Fermor, or as his friends lovingly call him – Paddy – ventures into a Germany on the precipice of a Nazi takeover and a severe decline into violence and authoritarianism. Enveloped in youthful naivete, Fermor only discerns the importance of impending symbols of doom in retrospect. He notes that one town he trekked through in the snowy prelude to Christmas “was hung with Nationalist Socialist flags” and that “the window of an outfitter’s shop next door held a display of Party equipment: swastika arm-bands, [and] daggers for the Hitler Youth.”

The unique timing of Fermor’s journey enables him to immortalize cities and towns fated to erupt in flames following devastating bombing campaigns, allowing him to forge connections with individuals later forever scarred by the memory of war. Viewing the past both through the rosy lens of nostalgia and the crystal clear lens of age-induced wisdom, Fermor recognizes both the fleeting beauty of the European landscapes he traverses through and the devastatingly dark omens glaringly scattered across the skies.

While centering his books around the changes between his pre and post war perspectives of Europe, Fermor extends one key thread throughout his books. Despite the violent fissures forged by war, Fermor remains convinced of the transcendent spark of familiarity and friendship which inextricably links each member of the human race.

Importantly, Fermor’s own experiences during World War II are indicative of his commitment to finding points of commonality with the most unlikely individuals. As a major in the British army during the war, Paddy coordinated resistance in German-occupied Crete and kidnapped Nazi General Heinrich Kreipe. Still, as the general remained hostage, Fermor recounts a moment in which both he and his enemy quoted lines of Horace together. He writes that it was “as though, for a long moment, the war had ceased to exist. We had both drunk at the same fountains long before; and things were different between us for the rest of our time together.”

Beyond reciting poetry with enemy generals, Paddy easily connects with many fascinating individuals. In Germany, he obtains an invite to an abandoned palatial estate; in Austria, he stays with a “plump and jolly” Frau Hubner, and in Hungary, he shares a roast chicken with a group of three friendly peasants under a heavenly hazel-clump. As Jan Morris, a Welsh historian, eloquently states, Fermor is “everyman, but in a particularly delightful kind.” He “makes friends whenever he goes, is as polite to tramps as he is to barons, repays all his debts, shows just the right degree of diffidence to his seniors, merriment to his peers, flirts with girls who give him duck eggs, gets drunk, hates hurting people’s feeling, and altogether behaves as a clever and gentlemanly young Englishman of the 1930s ought to behave.”

After spending a white Christmas in Germany, Fermor crosses the border into Austria. As he marches, he recites “a great deal of Shakespeare, several Marlowe speeches, most of Keats’s Odes” and “the usual pieces of Tennyson, Browning and Coleridge.” Intellectual and inquisitive, Fermor lands in Vienna, where he once again becomes cognizant of the social and political hemorrhaging befalling Europe. He writes that “it was a desperate time for Austria. All through 1933, the country had been shaken by disturbances organized by the Nazis and their Austrian sympathizers.”

A Time of Gifts closes on a bridge over the Danube forty miles from Budapest, yet Fermor’s journey extends further in Between the Woods and the Water. While he never reaches his final destination of Constantinople in this second sweeping travel memoir, he continues his tradition of imaginative curiosity and explorative wonder as he examines the histories and languages of diverse countries, traverses through enchanting landscapes, and weaves together elements of melancholic foreshadowing and exhilarating fun.

Still, at this point in his journey, Fermor was plagued by a “faint worry.” He writes: “I had meant to live like a tramp or a pilgrim or a wandering scholar, sleeping in ditches and ricks and only consorting with birds of the same feather. But recently I had been strolling from castle to castle, sipping Tokay out of cut-glass goblets and smoking pipes a yard long with archdukes instead of halving gaspers with tramps.”

Despite the fear of veering progressively further from his original mission in Between the Woods and the Water, Fermor develops an intimate relationship with his natural surroundings. Despite the importance of his disjointed rendezvous and spontaneous encounters – bonfires with gypsies, chases after Transylvanian girls in golden fields, games of bicycle polo on lawns of Hungarian counts – Fermor’s connection to nature shines through.

It is when he is alone with his thoughts, walking through tall rows of pines or along glimmering green lakes that he is most fulfilled. Sporadic conversations with woodsmen, innkeepers, and shepherds fill the liminal space between stretches of green, and it is in these moments when Jan Morris writes that Fermor’s “powers of recollection are given superb expression by the vocabulary of his other self, fifty years later, and we enjoy the incomparable riches of the Leigh Fermor style, a style of person as of prose.”

Between the Woods and the Water closes when Fermor reaches the border of Bulgaria. Still 500 miles from Constantinople, he ends his book with an enigmatic “to be continued.” Not fulfilling his promise to “pull [his] socks up and get on with it,” Fermor failed to publish his final book The Broken Road due to age-induced frailty. The Broken Road was released posthumously by his biographer, Artemis Cooper, and Colin Thubron, a distinguished British travel writer.

The Broken Road outlines Fermor’s travels in Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece. Far less refined, this closing book outlines the wilder world of the Balkans and beyond while also revealing the emotional frailty and human flaws of Fermor himself. No longer wedded to an absolute image of nobility, equanimity, and intellectual high-mindedness, The Broken Road delineates the paroxysms of emotion which conventionally befall 19-year-olds not yet accustomed to life’s winding road. Fermor gives way to revulsion, falls hopelessly in love with a Bulgarian girl named Nadejda, and finally feels the sharp pang of homesickness.

Full of Femor’s clever wordplays, hunger for knowledge, infectious desire for adventure, and precipitously eloquent powers of detailed description, The Broken Road is as unforgettable as its predecessors.

Following a brief stretch in Istanbul, Fermor visited Athens, where he met the first of a few great loves: Balasha Cantacuzene. A recently divorced, older Romanian painter and renowned beauty, Cantacuzene invited Fermor for a summer on her estate in Moldova until the war issued “marching orders out of paradise.”

In the aftermath of World War II, Fermor lived a nomadic life, venturing from England to Italy to Greece to France and sending a myriad of letters to the Duchess of Devonshire. As he outlines his aristocratic acquaintances and spends seemingly endless nights locked up in old castles, Fermor stitches his biting humor, colloquial charm, and intellectual prowess into his every sentence, proving that his undying charm lies not in his luxurious lifestyle but in his impressive scholarship and fierce zest for life.

Fermor and his wife Joan eventually settled in the Greek village of Kardamyli, south of Kalamata. Framed by olive trees, glistening blue skies, and rugged rocky beaches, their home became a placid refuge from the vicissitudes of everyday life and the perfect sanctuary for writing. During his peaceful years in Greece, Fermor published many books such as Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese and Roumeli: Travels in Northern Greece.

In his later years, Fermor continued writing, albeit slowly. He wrote articles, published travel reviews, and translated certain works into Greek, demonstrating his linguistic talents. On his 90th birthday, he was knighted, and eventually died on June 10th, 2011, eight years after his beloved wife passed away.

Now, Fermor leaves us with the vital reminder that the “true aim of existence” is “something to be pursued and loved in secret and behind barred shutters.” Through his beautiful prose, he nudges us out of our comfort zones and encourages us to find our own adventures.

While centering his books around the changes between his pre and post war perspectives of Europe, Fermor extends one key thread throughout his books. Despite the violent fissures forged by war, Fermor remains convinced of the transcendent spark of familiarity and friendship which inextricably links each member of the human race.

Katia Anastas is an Editor in Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She loves that journalistic writing equally emphasizes creativity and truth, while allowing...