Freeing the Student Press

NYS Senator Brian Kavanagh: Breaking a Legacy of Student Censorship

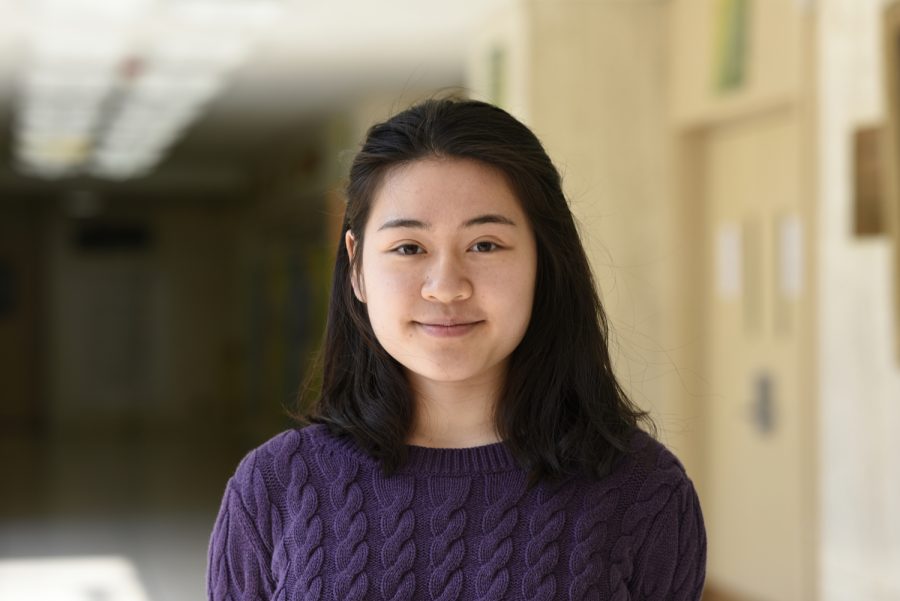

“Schools should prepare students for entering a world where one can leverage their vote and voice to fight for their beliefs,” said Alysa Chen, Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey.’

Do we age into our First Amendment rights? Some school administrations nationwide certainly seem to think so, particularly when it comes to student journalism.

On September 10th, 2018, students at Burlington High School published their first breaking story to their online paper, The Register: “Director of Guidance charged with six counts of unprofessional conduct.” By noon the following day, Principal Noel Green had the article removed. “It was our first big breaking story that no one else had,” co-author Julia Shannon-Grillo, 16, told the Burlington Free Press. “We are being censored,” commented co-editor Nataleigh Noble, 17.

In the spring of 2017, student journalists at Pittsburg High School looked into the qualifications of their new principal, Amy Robertson. “We wanted to be assured that she was qualified and had the proper credentials,” editor Trina Paul told The New York Post. Quickly, the journalists discovered Robertson’s former private school had been deemed “unsatisfactory” and shut down. Mysteriously, the college she’d claimed to get her master’s and doctorate degrees from, Corllins University, did not exist. “If students could uncover this, I want to know why the adults couldn’t find this,” Maddie Baden, 17, said.

Student journalists across the country take the initiative to uncover stories censored by their administrations. Do we age into our First Amendment rights? Did these students have the right to publish their findings? As of right now, the answers remain unclear. New York State Senator Brian Kavanagh is in the process of passing legislation shoring up the grey area.

Currently passing through New York’s Senate Education Committee, the Student Journalist Free Speech Act is designed to “protect student speech at educational institutions.” The bill both allows student journalists to publish responsible content without censorship and protects all employees who secure their students’ ability to do so. The purpose of the bill? To “expand freedom of speech and the press by giving final editorial control to student journalists at public high schools, while [encouraging] responsible journalism.”

I interviewed Senator Brian Kavanagh about how he realized student censorship was a problem that needed solving. “Initially, I heard about this bill from [New York State Assembly member] Donna Lupardo. She pointed out what seems to me to be a very big gap in our freedom of the press. High school journalists are not particularly protected,” the Senator told me.

“I have a very long- term commitment to open government and participant democracy. Student journalists play a very important role in that.”

Why the big fuss? What major contribution can student publications bring to the table? Jemma Lasswell ’19 and Alysa Chen ’19, both Editors-in-Chief of Bronx Science’s The Science Survey, told me that uncensored student publications are critical. “Censorship limits a school’s potential. If students want to write about something impactful, we have to write about things that are controversial. That doesn’t mean it has to be negative. Student journalists need to learn to take a nuanced approach on controversial issues and approach them with journalistic integrity,” Lasswell said. Chen agreed, adding, “I believe there is merit to facilitating difficult conversations between age groups who don’t necessarily agree with each other. With the recent global climate strike, young people across the nation expressed their dissatisfaction with other people’s passivity to the impending climate crisis. We are never too young for exercising our democratic right to free speech.”

“I believe there is merit to facilitating difficult conversations between age groups who don’t necessarily agree with each other. With the recent global climate strike, young people across the nation expressed their dissatisfaction with other people’s passivity to the impending climate crisis. We are never too young for exercising our democratic right to free speech,” said senior Alysa Chen.

The question of students’ rights to freedom of speech isn’t a new one. In 1969, Supreme Court case Tinker v. Des Moines sided with students wearing black wristbands to protest the Vietnam War, and is lauded as a case that cemented students’ First Amendment rights. But in 1988, in a 5-3 ruling, the Supreme Court held that a principal’s censorship of student publications “did not violate the students’ free speech rights.” The Court determined that the newspaper was intended to be a “limited forum” for journalism students to meet “the requirements of their Journalism II class,” and nothing more.

But Senator Kavanagh, Jemma Lasswell, and Alysa Chen view these student publications as multi-faceted forums designed to engage with and inspire the school community rather than simply to fulfill a class requirement. “No doubt, some people think we’re extending this right when students aren’t able to exercise it properly,” Senator Kavanagh said. “This is just the beginning of the conversation. We should be willing to give younger people the right to say things we might disagree with.”

Taylor Chapman is the Editor-in-Chief of ‘The Science Survey’ and an Academics Section Reporter for ‘The Observatory.’ The learning experience...