Pictured is a vintage, D-color grade circular diamond set in platinum. D indicates a colorless diamond, while letters further along the alphabet indicate diamonds that become progressively more yellow. (Photo Credit: CatherineLewis1976, CC BY-SA 4.0

Historically, dust made from finely-crushed diamonds has been used to polish and sharpen tools and weapons. Modern niches include high-end drill bits and semiconductors in supercomputers. While they’re known for being hard and tough, as no other mineral – except for another diamond – can give one a scratch, they don’t have much real purpose outside of a few, super-specific applications.

Diamonds are, ultimately, a crystal lattice of carbon atoms that derive their value from how difficult they are to find. They are too brittle to make anything durable out of. Even though they could withstand scratching and wear, a forceful blow might shatter one on impact. Like gold, they’re rare and shiny, which drives their price up far more than their durability.

Outside of high-end laboratory technology and specialized drilling equipment, diamonds aren’t used for much – except jewelry.

Promise rings, engagement rings, wedding rings, and ceremonial bands aren’t just pieces of metal and minerals, but one of the most important symbols in someone’s life. Their value can range from hundreds to hundreds of thousands of dollars (specialty pieces, usually bought by celebrities, can even cost millions), and are usually one of the first things on anybody’s mind when they talk about marriage. Even the proposal, which is the first confirmation of marriage, has become a ceremony in which the ring is the focal point.

Some believe that their value comes from the actual price of the ring – namely, the stone. Others believe that the value comes from the person who gives it. This has sparked much debate, especially around the practice of what sort of ring one should buy. The size, shape, and color of the diamond are all points to consider, but one of the biggest questions is where it should come from.

Because of ethical dilemmas – and incredible prices – the invention of lab-grown diamonds has offered a safe, cheaper alternative to buying the ‘real’ thing. While they may be identical to natural diamonds, the question of sentiment comes up again. Since they’re made in a factory rather than found in a mine, lab-grown diamonds are far easier to produce, and their availability depresses their value.

If someone truly loved you, would they not go all-out and spend a lot of money on the real thing? Does it actually mean the same thing as a natural diamond?

The other school of thought claims that because they look the same, they are the same. Plus, it saves labor many companies use to extract their stones, which is often harsh, immoral, or downright inhumane. One doesn’t have to spend money to be sentimental, and all that comes from buying a natural diamond in place of one grown in a lab is only a contribution to an artificially inflated market.

The idea started in the mid-20th century. In the 1950s, campaigns by companies claimed that a man would spend an entire month’s salary on a ring in order to show his love. Later, in the eighties, it jumped up to three months’ worth of salary.

The culprit? Many pin it on the De Beers company and their famous slogan, “A Diamond is Forever.” Called one of the greatest marketing campaigns of all time, De Beers still uses the slogan to this day.

Buying diamond rings was not really a tradition that people practiced throughout history. Some stories tell of Vikings using a ribbon to tie the bride and groom’s wrists together, symbolizing their bond, much like exchanging wedding bands does. In fact, the closest many have to monetary exchange is a dowry.

The idea that a bride could be sold or exchanged to another family for a gift – say, livestock, or valuable objects – may have served as the base of the idea that spending a lot demonstrates the groom’s dedication to his future wife.

De Beers capitalized on this sentiment, promoting the idea that the diamond ring was the new way to show affection. As one of the primary diamond producing companies, creating a use for diamonds by introducing the concept of a ring into everyday life skyrocketed their profits.

Of course, it didn’t come without a hefty price tag. One of their earlier slogans stated, “How can you make two months’ salary last forever?”

What they casually called “two months’ salary” was a significant amount of money for anybody to spend.

Already, they were pushing the idea that diamonds symbolize love, establishing their company as a household name – or, literally, as the company that made households by forging marriages. Love was something they could capitalize on, and marriage, an event that took much planning and was arguably the most important event of someone’s life, was an ideal place to station their product.

After all, diamonds represented the effort put into a relationship, and the resilience that a strong one could endure (as nothing could scratch or scuff their surface). By giving a ring to the bride, a groom could prove not only that he could support a new family, but also prove his dedication to ensuring that the marriage lasted.

Now, that number is around three months, and the prices of diamonds keep increasing. While the other aspects of a ring can all affect the price, the main point is the diamond itself.

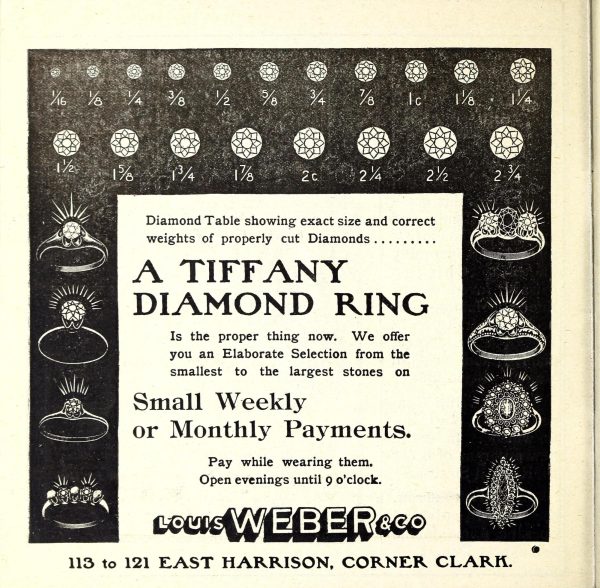

Diamonds are usually measured in terms of carats. One carat is about a fifth of a gram, and each increase brings an exponential increase in price. Larger diamonds are significantly rarer, especially the larger you go.

This is why some have encouraged buying diamonds of 0.9 or 0.8 carats. They look practically the same as full-carat diamonds, at least to the naked eye, and are significantly less expensive. They can differ in the thousands of dollars, with minimal visual difference.

Another way many save money is indicated by the increasing popularity of the lab-grown diamond industry.

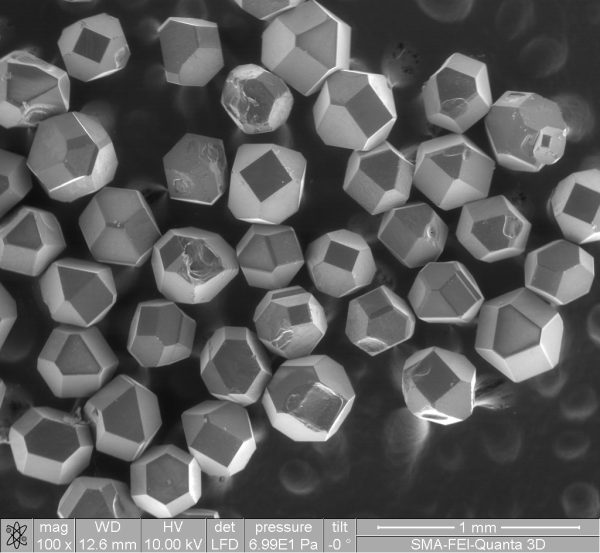

Diamonds are formed naturally in extreme temperatures and pressures, so the first attempts at making synthetic diamonds involved replicating those conditions. Using a small ‘seed’ of diamond in a shell of carbon, they would use over eight hundred thousand pounds per square inch of pressure (for comparison, atmospheric pressure is about 14.7 PSI) and heat well over a thousand degrees celsius it until the carbon atoms bonded to the structure. What they produced were miniscule pieces of carbon that could not be scratched.

These early methods of manufacturing synthetic diamonds, using high temperatures and pressures – named HPHT – required massive machines and huge amounts of energy that made the small gems they produced unprofitable.

Just a few years after the high-pressure high-temperature method was first successful, another, lower-cost process was designed; chemical vapor deposition, or CVD.

Similarly to the HPHT process, CVD begins with a diamond ‘seed’, but uses a fraction of the temperature and pressure. Instead, carbon gas is pushed into the chamber, and absorbs energy until it ‘ionizes’ – or breaks free from the gas form, and instead, settles on the diamond. The buildup of carbon atoms from this gas can take over a month for a one-carat diamond.

Each method has its advantages. CVD requires less energy, and is more chemically pure – as nitrogen impurities, which often happen during natural formation, too, are more common during the HPHT process. Since the gas introduced during CVD is specifically used to grow diamonds, they have fewer defects and are harder to distinguish from normal diamonds, while HPHT diamonds may have a few metallic impurities because of the process used to grow them. HPTP diamonds usually have higher average color grades, but CVD diamonds have higher average clarity grades.

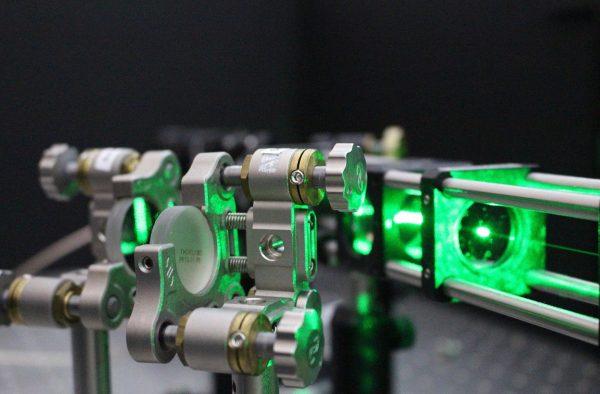

Both processes, however, produce chemically pure diamonds that are structurally identical to naturally-formed diamonds. They all have incredible hardness, are pure carbon, and will pass diamond tests – which rely on properties like how they interact with ultraviolet light, their thermal conductivity, and even their resonance to detect impurities in the structure.

In fact, one of the only differences between lab-grown and natural diamonds is the fact that they, both ethically and financially, cost less. Even if how much you spend denotes how much you care, you can still spare the moral price with something grown instead of mined with blood and sweat.

Diamonds are, ultimately, a crystal lattice of carbon atoms that derive their value from how difficult they are to find. They are too brittle to make anything durable out of. Even though they could withstand scratching and wear, a forceful blow might shatter one on impact. Like gold, they’re rare and shiny, which drives their price up far more than their durability.