Water Wars: Navigating the Complexities of Hydropolitics and Hydroterrorism in the Middle East

The systemic precedence for hydro hegemonic behavior in co-riparian states along with the emergence of hydroterrorism directly exacerbates the water scarcity crisis in the Middle East.

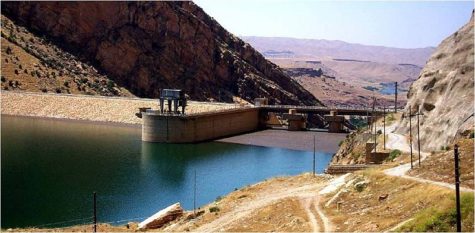

Sergeant James McCauley, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Located in northwestern Iraq, the Haditha Dam serves as a critical facility for generating hydroelectricity, regulating the flow of the Euphrates River, and providing local farmers water for irrigation.

More valuable than any of the region’s numerous natural resources, water is often referred to as the “liquid gold” of the Middle East. This simple necessity has become one of the divisive issues separating the co-riparian states of Turkey, Syria, and Iraq as water is essential to survival in the hot, arid climate. Sectarian tensions, humanitarian crises, and hydro-hegemonic behavior all contribute to conflicts over water distribution.

At the heart of these disputes is the concept of hydropolitics: the strategic use of water resources as a political tool. The Middle East is no stranger to hydropolitics, with various conflicts dating back centuries. But as population growth, climate change, and geopolitical tensions exacerbate water scarcity in the region, the stakes are higher now than ever before.

The two main rivers at the center of the control conflict are the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Roughly parallel to each other, the two rivers’ sources are within fifty miles of each other in eastern Turkey and their flow travels southeast through northern Syria and Iraq to the head of the Persian Gulf.

The flow of the Tigris and Euphrates depends heavily on winter rains and spring snowmelt from the Taurus and Zagros mountains. However, recent climate developments have threatened the stability of these water sources.

According to NASA data, the 2020-2021 rainfall season in the Middle East was the second driest in forty years. Groundwater storage is at an all-time low and sandstorms blanket the region almost weekly. Not only is there insufficient water for crop irrigation, there is often not enough water for household use.

The geopolitical tensions embroiling the region only aggravate this issue. Rooted in ethnic and historical conflicts, these conflicts sprouted as a result of inadequate treaties and resolutions. Following the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the Treaty of Lausanne, signed by Turkish, British, French, and other European representatives in 1923, established the borders of modern-day Turkey. Although the agreement resolved land disputes, it overlooked two critical issues: control of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and the creation of a Kurdish state.

In the years following the Treaty of Lausanne, Turkey, Syria, and Iraq each constructed dams and irrigation projects along the rivers, leading to disagreements over water usage and management.

In the 1970s, Turkey launched the Southeast Anatolia Project (GAP), a massive irrigation and hydroelectric project that aimed to develop the country’s impoverished southeast region. The GAP project included the construction of several dams and hydropower plants along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, which led to concerns from downstream countries, particularly Syria and Iraq, about water scarcity and reduced flow.

Journalist Alexandra Marvar stated, “Turkey has made a lot of powerful cases in favor of their hydropower network, from bringing the ability to irrigate crops in these arid regions to food stability to doing all of these theoretically positive things. But, ultimately, the network means cutting off the water supply to neighboring countries, taking water out of rivers that were already being heavily impacted by climate change, and changing the way that those rivers are able to supply people downstream with water.”

In response to this development, Syria and Iraq began to lobby for the establishment of international treaties that would regulate water usage and ensure equitable distribution. However, Turkey remained reluctant to sign such agreements, which led to increased tensions and even military threats between the countries.

In 1987, the three countries signed the Agreement on the Protection and Use of the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers, which established a framework for cooperation on water management. Despite this agreement, tensions continued to simmer, particularly during periods of political instability, when the effects of water scarcity became more pronounced.

In the early 1990s, the Turkish government completed the Atatürk Dam — the fourth-largest dam in the world — causing the forced resettlement of upwards of 50,000 people in a predominantly Kurdish region. By filling the Atatürk reservoir, Turkey cut off the majority of the Euphrates’ flow into Syria and Iraq for weeks, crippling agriculture. At virtually the same moment, then-President Turgut Özal asked Syria and Iraq to help combat the rise of The Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a Kurdish militant political organization and armed guerrilla movement.

The Kurds are an indigenous people of the Mesopotamian plains and the highlands in what is now south-eastern Turkey, north-eastern Syria, northern Iraq, north-western Iran, and south-western Armenia. They form a distinctive community, united through race, culture, and language, even though they have no standard dialect. Approximately thirty million Kurds live in the Middle East and comprise nearly one-fifth of Turkey’s population of seventy-nine million.

In the early 20th century, many Kurds had begun to consider the creation of a homeland — generally referred to as “Kurdistan.” However, such hopes were destroyed when the Treaty of Lausanne made no provision for a Kurdish state and left Kurds with minority status in their respective countries. Over the next 80 years, any move by Kurds to set up an independent state was brutally suppressed.

In the decades that followed, Kurdish-Turkish relations continued to deteriorate; democracy under President Erdoğan continued to backslide. Turkey’s grip on its neighbors’ fate through control of water only tightened, bringing drought to once-fertile Syrian and Iraqi farmlands, drying up entire villages, and forcing people to relocate to cities.

In recent years, the civil wars in Syria and Iraq have further complicated the management of the rivers, as various groups and factions control different parts of the river basin. The destruction of infrastructure and the displacement of millions of people also aggravates water scarcity as limited resources have to be allocated to more and more refugees.

The outbreak of the Syrian Civil War further strained relations between Turkey and Syria. During the war, the Damascus government switched sides to become a de facto ally of the PKK, which ultimately meant that Syria was retreating from an earlier agreement with Turkey to combat the movement and supporting a pro-Kurdish stance.

The outbreak of the Iraqi Civil War also increased tensions between Turkey and Iraq. Turkey has historically played an important role in Iraq’s politics and economy, especially through trade and investment. Turkey opposed the US-led invasion of Iraq and was concerned about the impact of the conflict on the wider region. The Turkish government also feared that the war would lead to the disintegration of Iraq and the emergence of a Kurdish state in the north, which could embolden Kurdish separatists within Turkey.

Ethnic consciousness generally increased in the region, growing disparities and rivalries as people become more competitive and nationalistic. Since then, Turkey has strategically cut off water supply from thousands of Kurdish villages in Syria and Iraq. It has also flooded entire Kurdish villages and settlements, weaponizing water and displacing thousands of people.

Marvar furthered, “All over the world we’ve seen big hydropower project sites being built on land that was very important to other cultures.”

For instance, the creation of the Ilisu Dam in 2018 inundated the 12,000-year-old settlement of Hasankeyf, a Kurdish heritage site with untold archaeological value. Continuously inhabited for more than ten millennia by the Byzantines, Romans, Mongols, Ottomans, and, for centuries, the Kurds, these civilizations’ artifacts and architecture were plentiful in this village. Hosting ancient cave dwellings, amphitheaters, aqueducts, mosques, and minarets, Hasankeyf had immense historical significance, yet was all wiped away for the sake of hydropower.

Through forcing relocation and subsequent cultural assimilation, water policy has helped the Turkish government exercise direct control over the Kurds in Turkey, and by controlling water flow to Iraq and Syria, indirectly controlling a much larger part of the Kurdish nation.

The emergence of terrorist organizations such as ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) and Al-Qaeda in the Middle East region has further complicated the hydropolitical equation. Both groups have used water as a tool to gain power and control over local populations.

Professor Nadhir Al-Ansari of the Luleå University of Technology in Sweden offered his insight. He stated, “ISIS and Al-Qaeda have tried to use water as a weapon. In fact, ISIS infamously occupied Mosul Dam and destroyed all the machines and all the technicians and engineers were ousted. ISIS also occupied a few other barrages in Western Iraq and flooded areas to stop the movement of the Iraqi army.”

The Mosul Dam, located in northern Iraq, is a crucial piece of infrastructure that provides electricity and irrigation to millions of people in the region. In August 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) captured the dam, which raised serious concerns about the safety of the facility and its potential for catastrophic failure. The occupation of Iraq’s largest dam by ISIS represented a significant threat to the people and infrastructure of the region.

The Iraqi government, with the support of the United States and other international partners, launched a military operation to retake the Mosul Dam. After several days of fierce fighting, Iraqi and Kurdish forces were able to recapture the dam and secure the facility. The successful operation to retake the dam demonstrated the importance of international cooperation in the fight against hydroterrorism in the region.

In fact, many scholars assert that international cooperation is the only method to resolving the hydropolitical tensions that dictate the survival of millions of civilians. Dr. Al-Ansari expanded, “The best mediator in the region would be the United States, followed by the European Union, and then the World Bank. Why have I picked these three? Because of their political influence on an international level, good technology that incentivizes countries to cooperate with them, and good financial support they can offer these countries.”

Yet, some also believe that real change cannot occur unless it is initiated by the Turkish, Syrian, and Iraqi governments themselves. For the crisis to be resolved, change needs to occur not just on an international level, but also on a local level. Another major reason why the water scarcity crisis is so intense in the region is due to the immense waste that occurs due to a lack of federal management of water sources.

In Turkey, 73% of the water resources are used for irrigation. Conventional irrigation methods are still the norm on most agricultural lands, leading to a great deal of water loss. Agricultural water use also pollutes surface and groundwater resources. Water pollutants can take the form of sediment, plant nutrition, soluble salts, agricultural chemicals, toxic elements, and pathogens. Chemicals delivered with irrigation water, fertilizers and pesticides also pose a pollution threat.

Turkey’s mismanagement of water has roughly reduced 40 percent of water flow into Syria. Currently, the water flow is only around 7,062 cubic feet per second (200 cubic meters per second) — less than half agreed in the 1987 protocol.

In Syria, huge quantities of water are wasted through inefficient irrigation systems such as flood irrigation, unlined and/or uncovered canals as well as evaporation from reservoirs. Even when the government has attempted to reform the country’s irrigation systems, Syria’s lack of public awareness initiatives has continued the cycle of mismanagement.

Dr. Al-Ansari added, “When they [the Syrian government] tried to change the irrigation technique from flood irrigation to sprinklers, they did not train the engineers and the farmers how to use the new techniques. So, there was a drop in agricultural activities because the farmers could not compete with the new techniques and there was about a 50% drop in agricultural production and farmers lost a lot.”

He noted that governments in the Tigris-Euphrates basins should adopt a multi-step framework for preparing an overall strategy. This includes designing a public water awareness program that includes promotional activities, implementing the activities, and monitoring and evaluating their effectiveness. Specifically, Al-Ansari concluded that the media could play an important role in raising awareness about the importance of water issues where the lack of public perception of the importance of proper water management directly causes misuse.

In Iraq, water waste emerges in its potable water distribution networks. The efficiency of the distribution network is one of the weakest transport systems in the world. Iraq’s distribution networks are old and deteriorating, with many pipes dating back to the 1960s. Leaks and ruptures in the pipelines have resulted in significant losses of potable water, while a lack of proper maintenance has led to contamination of the water supply. The poorly managed water distribution system results in unequal distribution of water across different regions and communities and an increased risk of waterborne diseases and food insecurity, as well as economic challenges resulting from decreased agricultural productivity.

It is evident that government action and public awareness projects are needed in the co-riparian states to address the gross mismanagement of water resources and combat widespread ignorance. Furthermore, some form of international cooperation must be formed to mediate the geopolitical and ethnic tensions surrounding the water scarcity conflict as well as suppressing the rise of hydroterrorism.

Ultimately, water is one of the most basic and essential needs for human beings. Access to clean and safe water sources is not just an amenity; it is a human right. It is only through effective delegation of water resources and cooperation that the co-riparian states can hope to secure a sustainable and prosperous future for their citizens.

The Middle East is no stranger to hydropolitics, with various conflicts dating back centuries. But as population growth, climate change, and geopolitical tensions exacerbate water scarcity in the region, the stakes are higher now than ever before.

Pritika Patel is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She believes that journalism serves as the vital connection between people and the world...