Change the Internal Narrative by Confronting Your Inner Critic

What does it take to muffle the negative thoughts in your head?

Riya Naskar, CC BY-SA 4.0

The inner critic gains its power from making you feel unsafe, warping your thoughts and reactions to fit a narrative that thrives from your most irrational panic.

Procrastination. Perfectionism. Pervasive anxiety. All of these struggles may fall under the looming and debilitating voice of the inner critic. The inner critic directly sways our mental wellbeing, magnifying mistakes and invalidating any achievements or hopes we possess. Having originated as controlling thoughts meant to cope with fear, these comments are deeply internalized and become penetrating negative self-talk.

In the context of cognitive behavioral therapy, the behavior of the inner critic is referred to as “automatic negative thoughts” (ANTs) and “negative self-talk.” The inner critic is persistent even at its most irrational and may take inspiration from critical people in the world around you as well as be influenced by your core values.

Perhaps the inner critic prevents you from starting a project or engaging in a stimulating conversation for fear of embarrassment. It may cause you to self-censor your insights, afraid of having an incorrect or unpopular opinion, or leave you struggling to know what in your mind to trust.

The inner critic can be harsh or sound deceivingly like the voice of reason. It may tell you that you are not ready or skilled enough for a certain task. It can demand perfection and bring out every perceived flaw. It can dwell on the past, leaving you floundering in regret.

Kendrick Perez ’26 added, “When I don’t live up to my expectations, it makes me doubt my ability a lot and makes me want to give up.” Fear of failure can paralyze, and a single mistake can make one feel woefully incompetent. The inner critic may judge clothing choices, body language, every word that exits your mouth until you cannot distinguish which voices in your head are accurate.

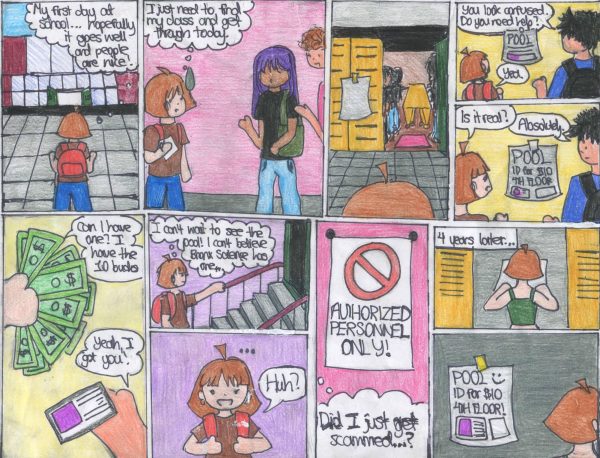

Author Denise Jacobs said, “The inner critic starts when we’re young. It is a psychological construct that develops at an early age and continues to develop throughout our lives. Adults have other coping strategies. When you’re a teenager, you’re closer to whatever initial trigger events caused you to develop [the inner critic]. Like when you were in first grade and your teacher was just like, ‘My God, you’re such a slob.’ And then you’re just like, ‘Oh, I’m a slob and I’m just sloppy.’ And all of a sudden you’re going to question that about yourself.” We internalize societal messages young, and soon they determine how we develop — even the foundation of our confidence and ability to self actualize.

It is a cultural norm to associate criticism with motivation; but instead, this form of communication more often promotes shame, guilt, and anxiety — the antithesis of motivation. In fact, it causes paralysis, stopping people from attempting tasks or seeking support. They quite literally cannot act or move to improve themselves.

The inner critic can convince people that they are so flawed that they are not worthy of human connection, one of the most basic forms of self-care. This causes avoidant tendencies, including procrastination and addictive behaviors, that help someone “stay safe” by not taking risks but, in this search for control, likely sacrifice joy and connection.

As Susmit Sen ’24 reflected, “Usually, I expect myself to perform [academically], but when I don’t, I feel very disappointed [in myself].”

The self-talk of the inner critic is typically rooted in either “bad self” or “weakness.” The bad self is motivated by shame, generating the feeling of being “unlovable; flawed; undesirable; inferior; inadequate; deserving of punishment; or incompetent,” in the words of “Working with Your Inner Critic” by PsychCentral. The weak self is intertwined with anxiety, codependence, submissiveness, and constant worry over a loss of control. Regardless of where it stems from, the inner critic invades mental health like a toxic virus making its way into the body and heightens pre-existing struggles.

Whether catastrophizing, attributing ill intent to others, or minimizing progress, the inner critic can make one feel perpetually on the verge of distress. It has even been tied to chronic anxiety disorders, another aspect of the mental health struggle.

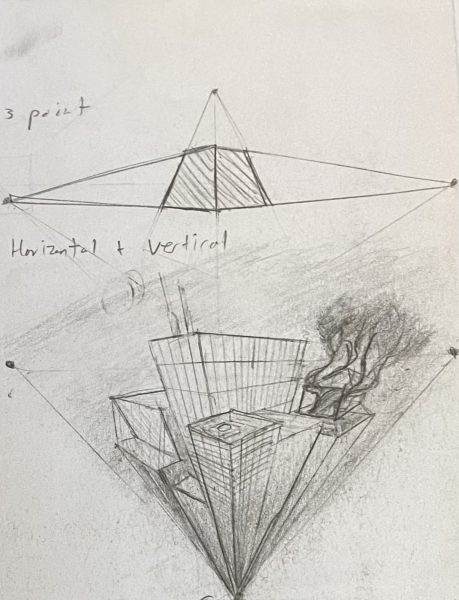

Psychologists attribute different causes to the inner critic. Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, ties it to the “superego,” one’s ideologies and inner sense of self that develop in response to others’ behaviors, predominantly those of parents. Simultaneously, we build an understanding of social cues and ethical norms, creating idealized versions of what our future selves should be. The superego can then tyrannize the ego — the brain’s basis for personality and reason — forming a false reality of unworthiness that causes retreat from the outside world.

Another explanation comes from brain structure: the distinction of the primitive “survivor brain,” made up of the brain stem, the oldest part of the brain, and the part to which the “fight-or-flight” response and physical survival are delegated. The “survivor brain” constructs narratives, analyzing surroundings to understand the outside world. For many children, consciously acknowledging the failure of adults in their lives is not possible, so this framing shifts internally —blaming oneself and one’s own behavior rather than that of those around them.

Consumed by fear of threats, it constantly compares surroundings to see what we may lack. This can be originally beneficial, guaranteeing human survival by identifying weaknesses physically and psychologically. As the brain develops, this is especially crucial in building a sense of security and knowing who to trust.

Unfortunately, this once-necessary coping mechanism for childhood may morph into a paralyzing factor of adulthood. Given its ties to the limbic system and amygdala, which control emotional responses and the emission of the stress hormone cortisone, the stress of the “survivor brain” can overtake one’s rational thinking.

However, the inner critic can be countered.

Recognizing inner critic-inspired behavior is the first step towards making change. It is not easy to identify the inner critic, a voice disguised as a rational part of your mind. Focus closely on what triggered it. The voice is self-destructive.

There are four main methods of tackling one’s inner critic: ACT, Positive Intelligence, CBT, and Self-Compassion.

The Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) approach, largely considered the most powerful method, emphasizes not changing negative cognitions but rather accepting them and thus letting them go. By delving into the root of your fears and acknowledging your vulnerability, you open the doorway to feeling your emotions in their entirety without the previous extent of shame. This disempowers the reach of the inner critic.

In this method, you must identify the inner critic, observe it, forgive your mind for thinking it, and let go of its pressures. Inner dialogue like “This is the inner critic talking” or ascribing a name to the inner critic — such as the “wolf” and the “demon” — can help you differentiate between these harmful thoughts and the tangible evidence surrounding you.

Jacobs stated, “…The thing that you really need is self-awareness. People tend to react to things — emotionally perceived threats, fears, things of that ilk — and they react without knowing why they react, right? They don’t have the self-awareness [necessary], because they haven’t done any inner work. And they lack understanding of their own motivations. So, I think the first thing is to start to develop a sense of self-awareness and honesty with yourself.”

We must remind ourselves that our thoughts are not fact-based but instead simply chatter and begin to view thoughts more objectively; for example, merely changing “I am not enough” to “My inner critic suggests that I am not enough” takes back so much power. By distinguishing the inner critic and characterizing it, you already separate yourself from many of its dangers.

Next comes the Positive Intelligence approach taken from Shirzad Chamine’s work that takes into account the “judge.” This label for the inner critic refers to constant judgment of ourselves, others, and larger circumstances. To combat this, Chamine advocates for the strengthening of the “sage brain,” shifting from a focus on the brain stem, limbic system, and amygdala regions to the middle prefrontal cortex, the empathy circuitry, and the right brain.

This uses short exercises rooted in the five senses, be it focusing on breathing, listening for sounds, or fixating on touch. The intention is to distract you from what is happening in your head, ground you in your body and the present, develop empathy with others and yourself, and reconnect with emotions.

The CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) approach weakens the inner critic by reinforcing the illogical and negative aspects of its behavior. Reason, therefore, can impede it, using charts, fact-checking, and analysis to see if its reactions and impacts are positive or negative and thus dissuade a person.

Building self-compassion is also key, being the classic “how would you treat a friend?” and using it to treat yourself with more kindness, like you would a peer in trouble. Reframing the narrative with a kinder—and more honest—attitude may decrease the strength of the inner critic.

Developing these strategies and finding what works for you may be daunting, especially while still building up a sense of self and navigating the burnout that comes with workload, which can be even more difficult in this post-pandemic reality for teenagers and adults alike.

Jacobs reflected, “I think in a lot of ways, what has been empowering for me in my own creative process professionally and with regards to the inner critic, is to really respect and honor all of my creative ideas and not judge them — to not be so critical of them and to give them a chance to have room to grow and breathe instead of judging them at the beginning — and I think that can be the recipe for avoiding burnout.”

The inner critic is not an accurate reflection of you. You are competent, worthy, and deserve to be loved.

It is a cultural norm to associate criticism with motivation; but instead, this form of communication more often promotes shame, guilt, and anxiety — the antithesis of motivation. In fact, it causes paralysis, stopping people from attempting tasks or seeking support. They quite literally cannot act or move to improve themselves.

Hallel Abrams Gerber is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey,’ using her writing to represent a myriad of social issues and innovations, bolster...