The ‘I’ in Academia

The objective in conflict with the self.

The first-person may also manifest itself as ‘we.’

That straight, fine, freestanding line. A single letter repurposed as a word, ambiguous if you think too hard. Though not an indefinite article, some would say it is indefinite. Absent of any curves, this line is permeated with such mystery and narcissism. So minuscule and so unnerving is this forbidden word ‘I.’

I take the succession “straight, fine, freestanding” from acclaimed Brazilian author Clarice Lispector’s debut novel Near to the Wild Heart, written shamelessly in a stream-of-consciousness technique and concerned with the interior self. These lines were compared to thoughts. These thoughts belong to the self, any self, no matter how derivative, unconventional, or inexplicable. They sustain to be thoughts, and we are thinking constantly.

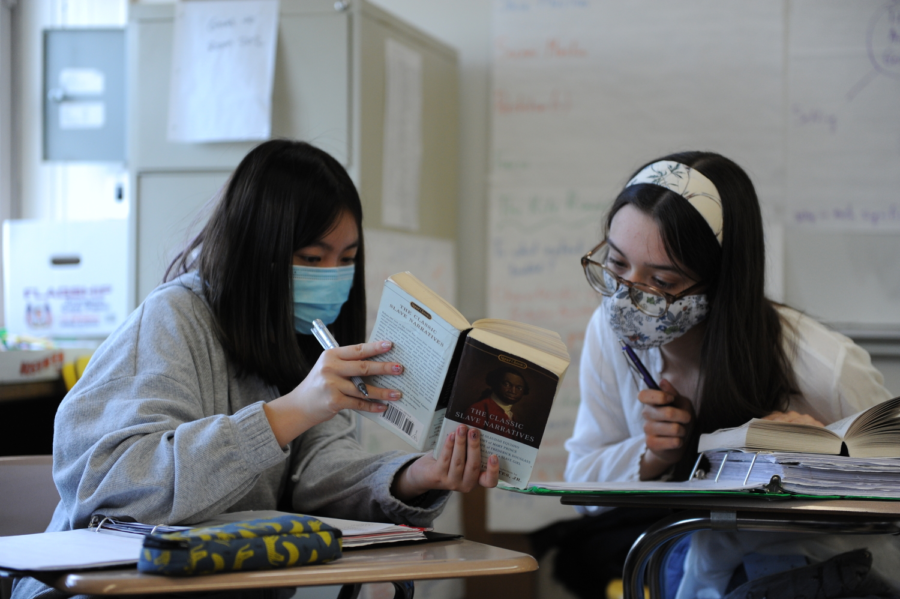

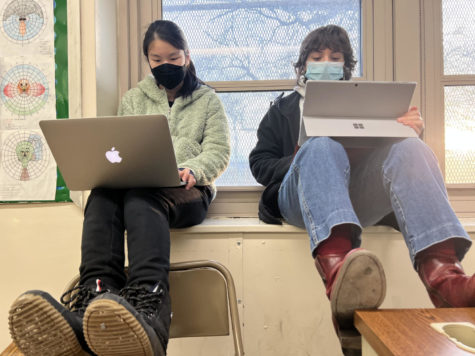

It is not often apparent that people are thinking from their exterior selves, but I have observed Selina Li ’22 as someone who speaks what is on her mind often, sometimes earning her the description of having “no filter.”

As I prepared a new section in my notepad to interview her, I asked her how her weekend was going that Sunday night. She told me about the new coats she and her siblings bought at the mall earlier that day and her plan to wear her new coat on Wednesday when the weather would be between the high 30s, low 40s. (Their mom disapproved of Selina’s twin brother and older sister’s coats, which is why they are going back to the mall next week. Their mom liked Selina’s coat. This made Selina smile.)

Before I could wield my journalistic questions, she landed on the topic of school herself and all the work she had to finish this Sunday night. One assignment she wanted to re-do for a better grade was for Mr. Nick McConnell’s AP English Literature & Composition with Creative Writing class. She had answered the other two questions, armed with the literary analysis skills of someone with years-worth of advanced education, but avoided the last one: “What did you learn as a writer of a personal essay that might be useful?”

“I don’t like using the word ‘I’,” Li said. “It makes me feel uncomfortable.”

An editorial published in The New York Times in April 2018 called “The Soul-Crushing Student Essay” laments college first-years’ hesitancies with acknowledging what the author refers to as “their large peculiarities.” When a student asks the author Professor Scott Korb of Pacific University what he considers “the clarifying question” (“Do you mean we can write with the word ‘I’?”), he notes, “The class looks up in wonder.”

To Selina, that question did not so much as ask her but interrogated her. Perhaps she believed herself not peculiar enough as a writer to answer the question. Though, it is odd that someone who does not find herself peculiar enough to write academic papers using the first person singular was able to make a very entertaining show of what she did over the weekend.

***

The word ‘I’ is one of the twenty-three oldest and most ‘ultra-conserved’ words across all Indo-European languages. Its estimated 15,000-year history arose from the shortening of the Old English word ‘ic.’ In the mid-13th century, ‘I’ as we write it today was permanently capitalized. This capitalization distinguished the word from its letter form to prevent potential misreading.

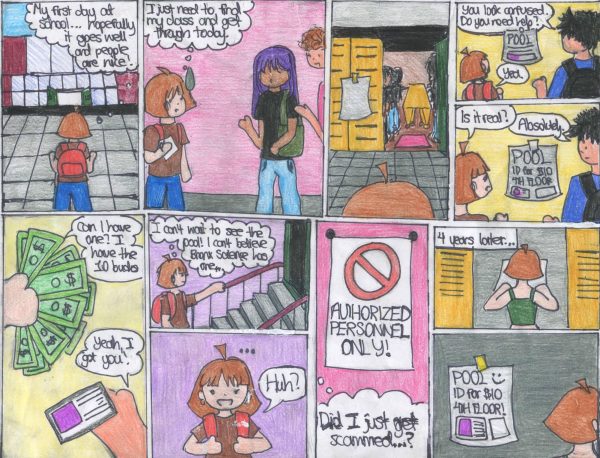

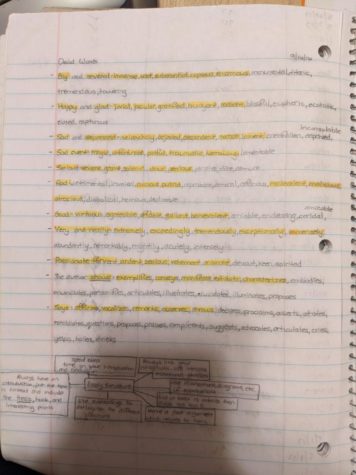

Despite this extreme conservation of the word over thousands of years, the use of ‘I’ was in the “no” pile for academic writing for most of my life. “Do not use ‘I’ in your essay,” I remember my sixth grade teacher announcing to my class, though it could have very easily been my fourth or second or eighth grade teacher. “It’s unprofessional.” My elementary and middle school teachers, particularly my English teachers, had a list of rules (sometimes regarded as sins) that my class needed to follow: no references to myself, no contractions, and no sentences starting with ‘but.’

And in seventh grade, there was a list of words that my class was not allowed to use in academic writing, the lines demarcating “yes” and a “no” never approaching some fogginess. My teacher called them “Dead Words.” She followed each “dead” word with another list of strong words to use as replacements. The snack could not be good. The snack had to be benevolent or cordial. The papercut could not be sad. The papercut had to be pitiful, harrowing, traumatic. The character could not say what was wrong with the dog. The character needed to propose, declare, or holler.

While my vocabulary may have undergone an expansion, and although I needed time to learn how to substitute “weaker” words for contextually “stronger” words, the certainty that was placed on this unwritten rule troubled me. Still, I replaced these weaker words instinctually.

As my relationship with writing has developed with age, the rigidity that I once felt with language broke down. High school teachers police the small technicalities of academic writing less (“Yes, you may use contractions” and “Do whatever you feel makes sense”). I am continually learning and experiencing the fluidity of language, writing to the rhythm rather than the rules. There still occurs in me a child-like happiness when these “rules” are broken.

I often go back to this passage in Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. Vuong writes, “I am writing because they told me to never start a sentence with because. But I wasn’t trying to make a sentence — I was trying to break free. Because freedom, I am told, is nothing but the distance between the hunter and its prey.”

***

Journalism seeks integrity and objectivity. Even while the biases in a human are inherent, there stubbornly exists the pursuit of objectivity. In the 1960s, the New Journalism movement followed non-traditional journalistic methods and emphasized more literary writing. It was clear to the reader that the writer birthed and coiled together the DNA strands of a piece.

The iconic member of the movement, Joan Didion, used ‘I’ less to subvert and more to attempt to understand the peculiarities and the lack of making up the world we live in. “I tell you this not as aimless revelation, but because I want you to know, as you read me, precisely who I am and where I am and what is on my mind,” she writes in her piece ‘In the Islands,’ originally published as a column for Life magazine, and then published in book form as part of her essay collection The White Album.

Critics of New Journalism cited clear subjectivity as potentially dangerous to the credibility of journalism. In that same vein, most academic papers in the sciences value the practice of objectivity.

The use of first person pronouns, while gaining acceptance among academics, does not necessarily equate to the personal. An analysis of the first-person from Duke University’s Thompson Writing Program advocates for the use of the first-person perspective. This is distinguished from a personal voice: “Writers can project a strong personal voice without using the first person, and they can write in the first person without writing personally.”

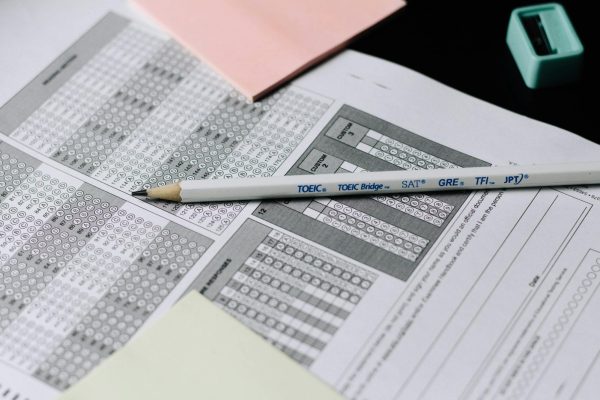

The APA Style Guide encourages the use of first-person pronouns for clarity. Edition 7 states that I can use ‘I’ but only to avoid the passive voice. In the Methods section of a paper, it is, “I surveyed 328 participants with Qualtrics. I used MATLAB to develop this multidimensional scaling algorithm. I split the specimen into three groups.” This is when ‘I’ becomes stale. Academia insists on practicality, on neat systems and structures. The debate seems to be more about what is acceptable, an attempt to define, rather than how humanity is impacted.

“You’re not writing about yourself. It doesn’t matter what you think. It only matters what the truth is,” said current MIT student and a 2020 Regeneron Science Talent Search Finalist Eva Xie ’20. “I don’t think humanity will be lost. The truth exists no matter how we try to communicate it.”

Social Science Research Teacher Mr. Joshua Fialkow acknowledges that guidelines, like grammatical conventions and established structures (Introduction, Methods, Results, Conclusions, then Discussion), may be constricting at times, but writing within set confines can help one to build structure and make a piece easier to read for peer review. “There’s a contention,” he said. “Is there too much conformity in terms of standards? At the same time, there is this standard that researchers have to meet to have [their papers] accessible for readers and for their own credibility.”

***

When I asked Bronx Science students what the word “academia” inspires in them, there seemed to be an internal clashing, creating a silent confusion — the ideals of academia as a concept colliding with now inextricably linked negative associations. As if reaching some evanescent conclusion, almost all I spoke to simply accepted their place in academic institutions.

Math Research student Kathryn Le ’22 and Biology Research student Jennifer Lee ’22 began to feel a disconnect between their research and themselves.

Le conducted research on ‘Caenorhabditis elegans,’ a type of worm, and its locomotion neural network, and Le is a 2022 Regeneron Scholar/Semifinalist, showing that success in academia is not always rooted in passion. “I feel distant from my research because I can’t see a real-world significance, and I don’t have a connection to what my results would become in the future,” she said. “I don’t really know why I’m doing it. I’m just doing it to do it.”

Finding her passion in neuroscience through her research on multiple sclerosis (MS), Lee sometimes felt frustrated by the sheer difficulty of it all and the detachment that came with only knowing participants based on whether they have MS. Lee and Le both specified how complex acronyms and supposedly some researchers’ attempts to impress a panel of their peers detracted from the readability of a paper.

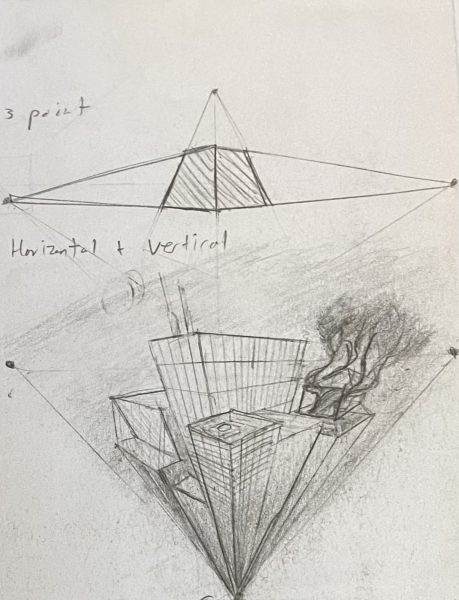

Tobias Alam ’22, who is a Math Research student and won 2nd place in last year’s Terra NYC STEM Fair in the Social Sciences category, worked on a program that drew from research papers across sources, such as Google Scholar and JStor, and generated new research questions likely to lead to scientific breakthroughs. His skepticism about academic conventions comes from historically unconventional methods of research, often research outside of institutions, that have significantly impacted what we now understand about the world.

While acknowledging his acquiescence to the rigid systems he argues against, Alam believes that academia can “institutionalize the way that knowledge can be acquired and knowledge can be expressed.” These papers that are being churned out may no longer belong to the creator but to power relations and institutions behind those papers.

The words in research papers should belong to the creator with a greater transparency that these words do in fact mean something to them. Emotions are the most basic mechanism for making decisions. Each word that we put down is a conscious choice, employing the virtues of academic objectivity — or not.

Alam continued, “The sole responsibility of academia is creativity, making things, inventing things — which is why it’s such a problem when instead of inventing things, everything is set in stone, just inscribed.”

The word ‘I’ is one of the twenty-three oldest and most ‘ultra-conserved’ words across all Indo-European languages. Its estimated 15,000-year history arose from the shortening of the Old English word ‘ic.’ In the mid-13th century, ‘I’ as we write it today was permanently capitalized. This capitalization distinguished the word from its letter form to prevent potential misreading.

Cadence Chen is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Science Survey.’ She enjoys journalistic writing for its artistic concision and sharp insights. Cadence...