Is the SHSAT the Problem, Solution, or Neither?

The lack of diversity in NYC specialized high schools has brought the Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT) under fire for failing to be inclusive of African-American and Latinx students. However, the overarching issue of segregation and unequal allocation of resources in public schools throughout NYC has been left largely unaddressed and there has been minimal action taken by the New York government to solve it.

Chukwuemeka Okonkwo ’20 believes that the SHSAT is an effective measure of intelligence and that it is a completely blind method of admission to Specialized High Schools, which may not be the case with other admission methods.

When under 11 percent of the ninth-grade seats for NYC specialized high schools were offered to African-American and Latinx students (with only 7 out of 895 seats at Stuyvesant being offered to African-American students), the SHSAT system came under fire for being discriminatory against students of color. In response to this disparity, there has been a movement from Mayor Bill DeBlasio and Chancellor Richard A. Carranza to eliminate the Specialized High School Admissions Test.

Mayor DeBlasio’s goal is to remove the SHSAT as the sole factor for admission into specialized high schools within the next three years, and instead admit the top 7% of NYC middle school students. Until the test is eliminated, DeBlasio hopes to make the specialized high school system more inclusive by expanding the Discovery program, a summer enrichment program for rising ninth-grade students who score within a certain range below the cutoff score on the SHSAT. This would reserve 20% of the seats at specialized high schools for disadvantaged students who score within a few points of the SHSAT cutoff, as opposed to the previous 5% of all seats. Students attending high-poverty schools, those at or above 60% on the City’s Economic Need Index, are classified as disadvantaged. His plan has been met with support from some NYC Council Members, as well as several advocacy groups. However, DeBlasio has also gained severe criticism from the public, particularly from the Asian-American community.

Although DeBlasio’s plan will increase diversity in these seven high schools, it does nothing for the larger underlying issue that has been prevailing for years. Despite being very politically liberal and one of the most diverse cities in the U.S., the NYC school system continues to be one of the most segregated in the country and the education quality of our schools is far from equal. There have been minimal integration efforts in elementary and middle schools and there continues to be a racial divide between students of all ages.

While the range of students attending advanced or special schools is diverse, the schools themselves are largely segregated. According to the study highlighted in the article “New York State’s Extreme School Segregation: Inequality, Inaction and a Damaged Future” by John Kucsera and Gary Orfield, although New York Magnet schools are largely multiracial and have a low proportion of segregated schools, “17% of magnets had less than 1% white enrollment and 7% had greater than 50% white enrollment, with PS 100 Coney Island having a white proportion of 81%.”

The issue of diversity is not unique to the specialized high schools; it is prevalent throughout New York City.

The SHSAT has been in place for decades as part of the application to specialized high schools, but when it was made the sole determinant of what students would be admitted to specialized high schools in 1971, it received a great deal of backlash. Even now, the test is accused of being “culturally biased” and discriminatory of students in certain demographics.

Yet, the SHSAT itself is not the problem, and removing it is not an effective solution.

The SHSAT contains neutral questions that are aimed to test students’ proficiency in certain subjects, and is race and income-blind. What is not so blind is the allocation of resources to zoned schools, particularly those in areas with high African-American and Latinx populations.

It is absolutely necessary to integrate schools at all levels throughout NYC, and to commit resources to providing equal, high-quality education to all of these schools. There can never be equality in separation.

However, this will be a long and grueling process, and it will take time for the state of the NYC public school system to improve (not to mention that as of right now, any integration efforts have been meager, at best).

A far more immediate solution would be to provide free test preparation to high-poverty and high-minority-populated schools, and to raise awareness for access to these resources.

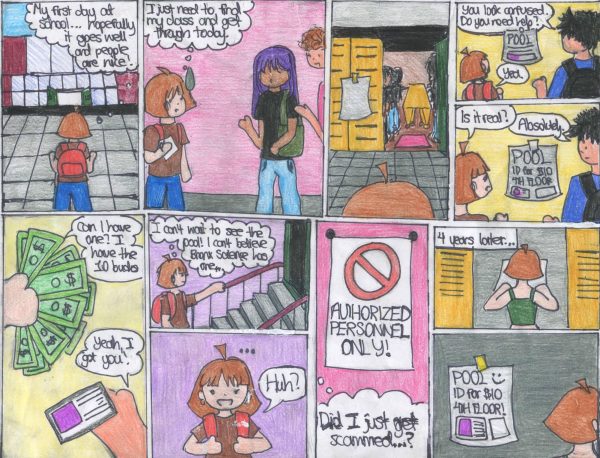

In addition, although it may seem like an effective solution to admit students based on their grade ranking, this system could put many intelligent students at a disadvantage.

Many Bronx Science students feel that the SHSAT is a fair measurement of preparation for a specialized high school, and should not be taken away.

“I believe the SHSAT is a good way for someone who didn’t try so hard in middle school to be admitted solely based on their intelligence, no other factors,” said Chukwuemeka Okonkwo ’20. Having succeeded on the SHSAT without receiving tutoring or attending test preparation class, Okonkwo believes that the test can be an accurate measurement of a student’s intelligence.

Prioritizing admission by student performance in middle school also has the potential to directly harm certain students’ chances of acceptance.

“[Grade-based admission] may disadvantage students who have become victims of excessive disciplining which have affected GPA, or other ways in which race negatively impacts the grades of students of color,” said Isaac Rjavinski ’20.

Admittedly, the SHSAT does need to be reformed in a way that is more similar to an IQ test than a knowledge test, but even in its current state it may be more effective than comparing students’ grades.

“Often times the smartest students are those who are “bored” with the learning pace in elementary and middle schools so they don’t try to do well. The rigorousness of schools would also play a part in their application, and it complicates things far too much,” said Okonkwo. “The SHSAT is a good way for someone who didn’t perform so well in middle school to be admitted solely based on their intelligence, no other factors, and it is as blind as a bat.”

Under the Hecht-Calandra bill of 1971, admission to The Bronx High School of Science, Stuyvesant High School, and Brooklyn Technical High School, as well as other similar specialized high schools, must be based off of a competitive, objective scholastic achievement examination. In order to remove the SHSAT and implement his plan, Mayor De Blasio has been attempting to pass his own bill through the New York State Senate in Albany, since the test is protected by New York State law. Unless De Blasio’s bill is approved, which may not happen within the next few years, the SHSAT must remain in place as the sole factor of admission.

“[Grade-based admission] may disadvantage students who have become victims of excessive disciplining which have affected GPA, or other ways in which race negatively impacts the grades of students of color,” said Isaac Rjavinski ’20.

As it is enshrined in state laws, the SHSAT is the one issue that Mayor De Blasio cannot control. The time and resources that have been dedicated to attempting to alter the alleged fairness of the SHSAT would have been better used to determine ways to provide underprivileged students with education and preparation for the test, and to begin to work on improving the quality and diversity of elementary and middle schools throughout New York City.

Although Mayor De Blasio is right to address the racial disparity in specialized high schools, it seems that he either has a fundamental misunderstanding of the underlying issues behind such a lack of diversity, or he is not willing to put in the funding and effort that is necessary to significantly improve the overall state of New York City public schools and benefit the students who rely on them for their education.

Darya Lollos is a Managing Editor for the ‘Science Survey’ and an Academics reporter for ‘The Observatory’. Journalism within Bronx Science keeps...

Nate Lentz is a Photo Editor and Chief Photographer for ‘The Observatory.’ Nate has always had a great appreciation for the world around him, and uses...