Remembering Lucasfilm’s ‘American Graffiti’ (1973)

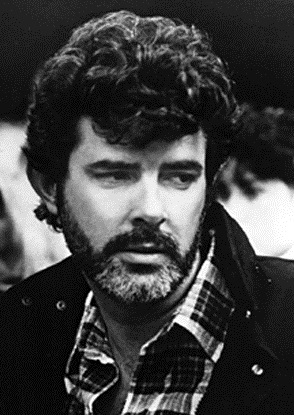

Despite being released nearly fifty years ago, George Lucas’ coming-of-age film still resonates with younger generations today.

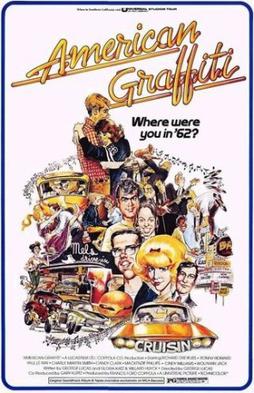

Here is the film poster for ‘American Graffiti’ with illustrations of scenes in the movie. The caption reads, “Where were you in ’62?”

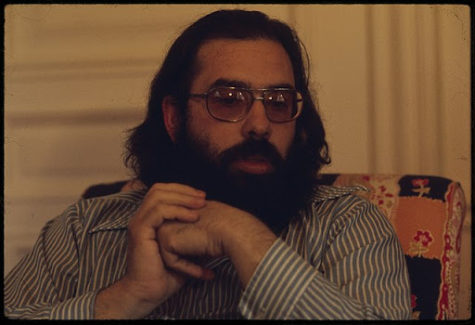

Film juggernauts George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola kick off the coming-of-age film American Graffiti with Bill Haley’s ‘(We’re Gonna) Rock Around the Clock.’ The tune is played by the famous (and real) disc jockey Wolfman Jack, who continuously plays a stream of rock n’ roll in the background of the adventures of four adolescents in a small southern California town.

The entire night of adventure takes place before two friends, Curt Henderson and Steve Bolander, are meant to catch a plane ‘back east’ to attend college for the next four years. Henderson and Bolander, along with their friends Terry ‘The Toad’ Fields and John Milner, spend their last evening of summer vacation cruising around, forging new friendships, and confronting the reality of change.

George Lucas, now famed for creating the Star Wars franchise, had his directorial debut with a science-fiction film named THX 1138. With this film, Lucas would work with producer Francis Ford Coppola who was, at the time, chartering the New Hollywood movement in the seventies. Coppola had then encouraged Lucas to create a film that would appeal to a greater mainstream audience. The idea of creating a coming-of-age film based on his own teenage experiences in the early sixties in Modesto, California was compelling to the naive director. Taking some inspiration from his previous work in college, including a proposed documentary about disc jockey Wolfman Jack, Lucas began developing Another Night in Modesto.

The film, in part, was semi-autobiographical to George Lucas’ experiences throughout his adolescence. While Curt Henderson was meant to represent Lucas throughout college, John Milner was based on his own street racing years and an ode to Kustom Kulture in Modesto. Similarly, Toad Fields’ ‘bad luck’ in dating was meant to reflect Lucas’ own experiences as a ninth grader in high school. Lucas also took heavy inspiration from the Italian comedy film, ‘I Vitelloni’ which also documents a night of several friends before a massive change in their lives.

George Lucas, along with Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, created a pitch for production companies and changed the name of the film to American Graffiti. Despite their many attempts to pitch the film for financing, many studios refused. The basic premise of a coming-of-age film was not necessarily appealing in terms of profit, and many producers expressed concerns over music licensing costs.

Despite many attempts on behalf of others to morph what was George Lucas’ vision of American Graffiti, he remained firm in his proposed screenplay. These creative differences were prominent when Lucas had hired former colleague Richard Walter to aid in writing the screenplay for the film while he pursued other projects. When Lucas had returned, Walter had written the screenplay in the style and tone of an exploitation film, similar to John Brahms’ Hot Rods to Hell. Lucas took a distaste for this version of the script: “It was overtly sexual and very fantasy-like, with playing chicken and things that kids didn’t really do.” Walter was fired, and Lucas had written the first draft of the script by himself in a matter of weeks. Using his extensive reserve of vintage records, Lucas had written each scene with a specific song as the backdrop.

United Artists had refused the script Lucas had produced for two reasons: one, it was too costly to license all seventy-five songs Lucas wanted to feature in the movie, and two, it was too experimental. American Graffiti was described as follows by United Artists: “A musical montage with no characters.”

With initial disapproval by American International Pictures because the film was not ‘violent or sexual enough,’ Lucas found favor at Universal Pictures. Lucas was given entire artistic control over the film, under the condition that it would be produced on a very low budget. American Graffiti was originally given a $600,000 budget, but was given an additional $175,000 when producer Francis Ford Coppola signed on. Coppola’s smashing success with the film The Godfather would allow Universal Pictures to advertise this small coming-of-age film to greater success.

The original setting of American Graffiti was intended to be Lucas’ own hometown, Modesto, California. However, the actual film itself was not filmed in Modesto as the director believed the town had changed too much. To capture the lost American culture that Lucas had nostalgically remembered from his adolescence, the film was shot in the small town of Petaluma. ‘Mel’s Drive-In’ where the four friends meet in the first shot of the film was in San Francisco, and many of the cruising shots were filmed in San Rafael. However, due to the shooting delays and disruptions to local businesses in San Rafael, the city council withdrew the permission Lucas had to film.

But despite the problems with filming, namely two camera operators being nearly killed during the climatic race scene at the end of the film, American Graffiti was released as a critically acclaimed film. While the film had cost only about 8.2 million to produce and market, it yielded worldwide box office revenue of about 336 million (adjusted for inflation). Because of the massive sleeper success American Graffiti had seen, producer Francis Ford Coppola had regretted not financing the film himself. Lucas recalls: “He would have made $30 million (equivalent to $183 million in 2021) on the deal. He never got over it and he still kicks himself.” At the time of its release, American Graffiti was the 13th highest grossing film of all time in 1977.

George Lucas gave us American Graffiti forty-six years ago. It is hard to believe that a film created in efforts to reminisce about the early sixties would be appreciated even today, but American Graffiti remains true to the adolescent experience. Curt Henderson is our main protagonist who is reluctant to leave for college: “It doesn’t make sense to leave home to look for home”; Steve Bolander finds excitement in leaving the ‘deadbeat’ town: “You just can’t stay seventeen forever!”; John Milner just wants everything to stay the same: “Rock and Roll’s been going downhill since Buddy Holly died!”; and Terry ‘Toad’ Fields grapples with being the unwanted, comedic relief. Lucas, in his staunch efforts to avoid succumbing to cinematic sensationalism and exploitation, would create a film that is a realistic depiction of growing pains. Although it was difficult for such a film to be produced, Lucasfilm had pushed it through Hollywood, and it was appreciated. The simple premise in the absence of sex, drugs, and violence is what makes this film so universally true and beautiful.

Lucas created this film as a love letter to a time when teenagers acted how they were meant to act — like teenagers. Young adults straddling the line between childhood and adulthood, looking awkward and feeling melancholy. But by navigating the tumultuous seas that is adolescence, Lucas’ characters find themselves completely and thoroughly enjoying themselves. As Curt Henderson goes about the night, unsure whether or not he will board the plane to his new life, he finds himself freer than ever before. The prospect that nothing is set in stone governs him as he cruises with a group of greasers called the Pharaohs or while he chases the girl of his dreams in a Ford Thunderbird.

And before an age dictated by technology, teenagers enjoyed the more simple pleasures of life. The general intrigue that Wolfman Jack produces as he spins discs throughout the night is indicative of the simple pleasure Lucas’ characters derive from music. Music is among one of the most important parts of American Graffiti that makes it so stylistically unique. The music played in the film is regarded as diegetic music that the characters themselves can hear, and are thus, affected by. We see this when John Milner hears ‘Surfin’ Safari’ by The Beach Boys play in his Ford Deuce Coupe — he immediately shows distaste for ‘modern music’ and yearns for the old rock and roll of Buddy Holly and Richie Valens.

The dilemma of whether or not Curt Henderson is to attend college and leave his old life behind reflects the incoming change that will affect the entire nation. The night documented by American Graffiti is filled to the brim with unlikely friendships, quick laughs and heart-warming moments but is sobered at the end of the film. As the futures of the four main characters are shown, the audience is made aware that the dorky, lovable and vulnerable Toad Fields is bound to be found missing in action in Vietnam.

American Graffiti is a forewarning regarding the loss of innocence in the face of violence and war. But unlike other anti-war films, Lucas avoids the glorification of war itself by celebrating the joys of innocence as one comes of age. It reminds us bitterly that those who are sent to fight our wars are but children themselves.

Curt Henderson boards the plane to attend college back east. As he peers out of the plane window, he sees the ‘angel’ he had searched for all night. The view from the plane is a bittersweet one, as he leaves his old, familiar life behind for a new one. But despite all the blondes in white Thunderbirds we may leave behind, sometimes all we need is a little courage to leap from a place of comfortability to seek adventure.

Watch George Lucas’ American Graffiti HERE. (Subscription required)

Listen to “Highlights from the Soundtrack of American Graffiti” HERE. (Subscription Required)

American Graffiti is a forewarning regarding the loss of innocence in the face of violence and war. But unlike other anti-war films, Lucas avoids the glorification of war itself by celebrating the joys of innocence as one comes of age. It reminds us bitterly that those who are sent to fight our wars are but children themselves.

Karishma Ramkarran is an Editor-in-Chief for ‘The Observatory’ yearbook and a Staff Reporter for 'The Science Survey' newspaper. She appreciates journalistic...